Making your house “smart” could soon become cheaper and easier, thanks to new technology developed by researchers at the David R. Cheriton School of Computer Science.

Their recent study describes an approach that can be used to deploy, for the first time, battery-free sensors in a home using existing WiFi networks. Previous attempts to use battery-free sensors ran into some obstacles, making the efforts impractical. These hurdles include the need to modify existing WiFi access points, challenges with security protocols, and the need to use energy-hungry components.

L–R: Postdoctoral fellow Ali Abedi, Professors Tim Brecht and Omid Abari, master's candidate Farzan Dehbashi with the WiTAG WiFi-based backscatter system they developed (one device held by Tim Brecht and another by Farzan Dehbashi)

“If you look at the current sensor products, they need batteries, which nobody likes to have to change, but they will work with commodity WiFi,” explained Cheriton School of Computer Science Professor Omid Abari. “There has been recent research, which proposes approaches that don’t need batteries. But while they’re addressing the battery problem, they’re adding another issue — it doesn’t work with commodity WiFi devices.”

“So, our approach combines the best of these two worlds — it is battery-free and it works with commodity WiFi devices.”

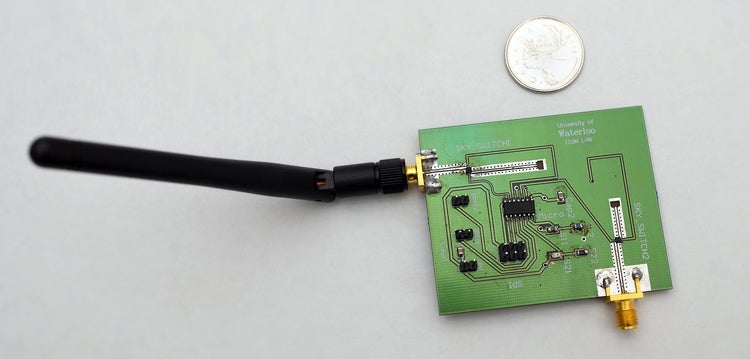

WiTAG is a WiFi-based backscatter system for existing WiFi networks. It enables a battery-free tag to communicate data to existing WiFi devices without requiring any modifications.

The

new

communication

mechanism

outlined

in

the

study,

called

WiTAG,

could

revolutionize

the

smart

home

industry

as

the

Waterloo

researchers

have

shown,

for

the

first

time,

that

battery-free

sensors

can

be

used

with

common

WiFi

access

points.

WiTAG

will

enable

the

use

of

regular

WiFi

devices

for

reading

data

from

smart

devices,

unlike

existing

products

that

use

power-hungry

WiFi

transmitters

to

send

their

data

and

therefore

require

the

use

of

batteries.

WiTAG

uses

radio

frequency

(RF)

signals

as

a

power

source

and

makes

use

of

existing

WiFi

infrastructures

to

read

data

from

sensors

without

requiring

the

sensors

to

be

connected

to

the

WiFi

network,

which

makes

them

much

easier

to

deploy.

This

allows

smart

home

technologies

such

as

temperature

sensors,

light

sensors

and

potentially

wearable

devices,

such

as Fitbits

and

those

that

monitor

heart

rate

and

glucose

levels,

to

use

the

WiTAG

system.

“One

of

the

biggest

breakthroughs

is

the

fact

that

our

technique

works

with

encryption

enabled,”

said

Cheriton

School

of

Computer

Science

Professor

Tim

Brecht.

“The

prior

proposed

techniques

for

battery-free

communication

do

not

work

with

encrypted

WiFi

networks,

meaning

that

your

WiFi

network

could

not

use

a

password,

which

no

one

wants.”

The

researchers,

who

have

filed

a

provisional

patent,

implemented

WiTAG

and

created

the

first

prototype,

are

now

working

on

a

second

prototype.

They

are

also

developing

an

app

that

will

work

with

the

system

and

have

plans

to

support

a

wide

variety

of

applications.

“By

having

the

application

running

on

a

phone

without

any

other

modification

either

to

the

phone

or

to

the

access

point

we

can

read

sensor

data,”

said

Ali

Abedi,

a

postdoctoral

fellow

at

the

Cheriton

School

of

Computer

Science.

“Data

can

be

read

from

things

such

as

temperature

sensors

or

anything

you

see

in

smart

homes.”

A

paper

describing

the

system,

titled

WiTAG:

Rethinking

Backscatter

Communication

for

WiFi

Networks,

co-authored

by

Abari,

Brecht,

Abedi

and

Mohammad

Hossein

Mazaheri,

a

research

assistant

at

Waterloo,

recently

appeared

in

the

Proceedings

of

the

17th

ACM

Workshop

on

Hot

Topics

in

Networks.