Computer scientists at the David R. Cheriton School of Computer Science have found a novel method to help travellers protect sensitive information from border control agents.

Shatter Secrets allows a person to encrypt their electronic device’s password, which is then split up by the app and sent to people at the point of destination. To get the password, the travelling party has to visit people they chose to have a share of the encrypted password and tap their devices to the secret keepers’ phones.

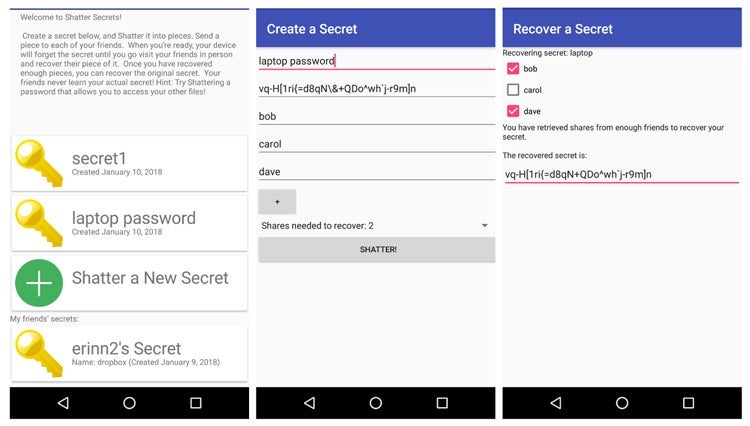

Shatter Secrets running on an Android device showing, from left to right, the list of created secrets and shares received from friends, the configuration screen for sharing a new secret, and a secret being recovered after retrieving shares from two of three friends.

Modern consumer electronic devices are full of confidential personal data, such as past conversations, photos and videos, medical information, and passwords for services that contain information on our entire lives. This makes the devices of particular interest to law enforcement officials during even routine searches. A specific threat to users is when crossing international borders, as reports have emerged that the data on these devices is subject to search and seizure without warrants or even suspicion of wrongdoing. In some cases, travellers have even been compelled to provide PINs, passwords, encryption keys, and fingerprints to unlock their devices.

“We argue that international border security agents have no business rifling through the intimate data stored on our personal electronic devices without a warrant or consent,” said Atwater, a PhD candidate in the Cryptography, Security, and Privacy (CrySP) research group at the Cheriton School of Computer Science. “By distributing encryption keys amongst trusted friends at the traveller’s destination before travel, the traveller cannot be compelled to provide access to their devices immediately.”

“Shatter Secrets is deliberately intended for people, such as journalists and activists, who have high-value information and would rather be subjected to government questioning than give up the data they’re trying to protect.”

Shatter Secret uses threshold cryptography to distribute encryption keys into shares, which are then securely transmitted to friends residing at the traveller’s destination. When a traveller is subjected to scrutiny at the border, they are physically unable to comply with requests to decrypt their devices.

“We do not want people to be put in a position where they have to be lying, so one of the things we wanted to ensure is that when you say you cannot get your data, it is true,” said Ian Goldberg, a professor in Waterloo's Cheriton School of Computer Science. “But even persons who don’t cross borders or don’t think they have much to hide should be glad that there is a technique for journalists and activists to protect themselves. The protection of everybody’s civil rights and the protection of democracy hinges upon a free and open press and activists who are willing to push boundaries and effect social improvement.”

Open Privacy is an incorporated non-profit society in British Columbia that researches, builds and deploys technology that serves marginalized communities. Donations to Open Privacyhelp fund projects such as Shatter Secrets as well as research and day-to-day running costs.

To learn more about this innovative research and the app, please see Erinn Atwater and Ian Goldberg’s paper, Shatter Secrets: Using Secret Sharing to Cross Borders with Encrypted Devices, which they presented at the 26thInternational Workshop on Security Protocols in Cambridge, UK, March 19–21, 2018.