10. Boolean Formulas

We can make some progress in proving Boolean circuit lower bounds by considering restricted classes of circuits. One such natural restriction is the one leading to Boolean formulas.

Definitions

A Boolean formula is a Boolean circuit with one important restriction: all of the gates have only one output wire. In other words, the output of each gate can only be used as the input of at most one other gate. (This property of formulas is sometimes called the bounded fan-out restriction.)

A Boolean formula has bounded fan-in when each of the \(\wedge\) and \(\vee\) gates have exactly two inputs. In this lecture, we will consider only Boolean formulas with bounded fan-in.

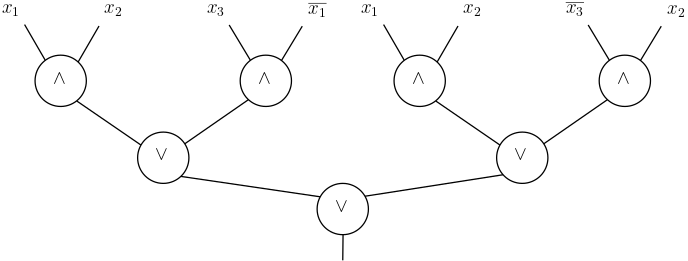

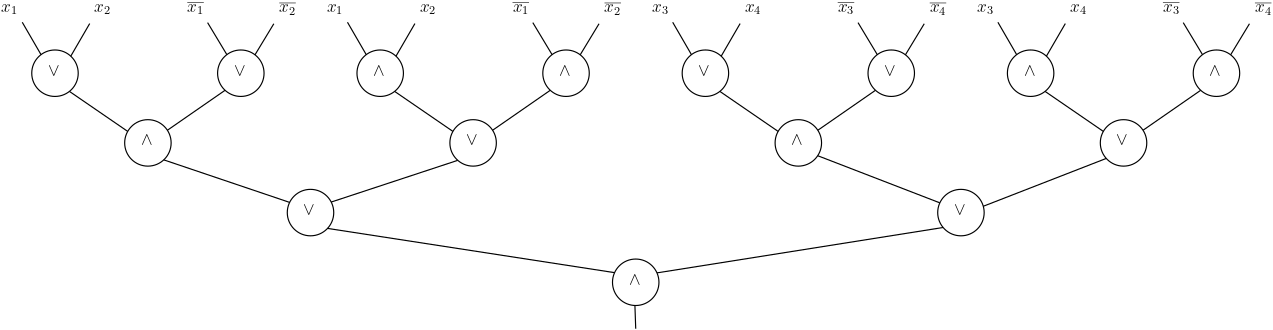

Just as we did with circuits, we can represent Boolean formulas with bounded fan-in as a directed graph with nodes representing the gates of the circuit. In this case, it is most convenient to write formulas as rooted (binary) trees of \(\wedge\) and \(\vee\) gates with multiple copies of the literals \(x_i\) or \(\neg x_i\) as the leaves of the tree. Here, for example, is a Boolean formula with bounded fan-in computing a function on 3 bits:

(In general, we could consider a slightly more general-looking notion of Boolean formulas by allowing the negation gates to be placed anywhere in the circuit instead of being applied only to the input variables, as in the example above. However, by applying De Morgan’s laws we see that without loss of generality we can always “push” the negation gates towards the leaves without affecting the number of \(\wedge\) or \(\vee\) gates of the formula or the function that it computes.)

The natural notion of size of a Boolean formula is again the number of \(\wedge\) and \(\vee\) gates that it contains. But, as it turns out, this number of gates is always exactly one less than the number of leaves in the tree representation of the formula. So we can equivalently use the notion of leaf-size of a Boolean formula with bounded fan-in to represent its complexity. This is what we do, letting \(L(F)\) denote the leaf-size of the formula \(F\). The formula complexity of a Boolean function \(f \colon \{0,1\}^n \to \{0,1\}\) is then defined to be

\[L(f) = \min \{L(F) : F \mbox{ computes } f\}.\]First Examples

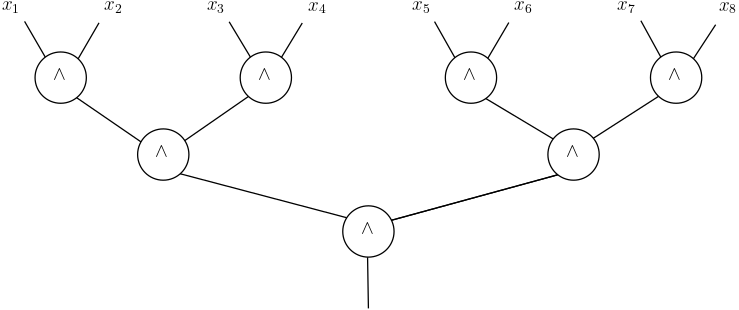

As a warm-up exercise, let’s consider the \(AND_n \colon \{0,1\}^n \to \{0,1\}\) function. The formula complexity of this function is \(L(AND_n) = n\). The upper bound is given by the formula

And the matching lower bound follows from the observation that every function that depends on all \(n\) of its input bits (as is the case with the AND function) must have leaf size at least \(n\), since each of the variables \(x_1,\ldots,x_n\) (or their negations) must appear in at least one leaf each.

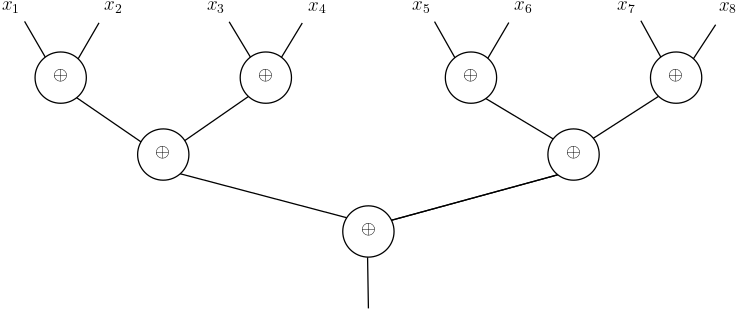

A slightly more interesting example is obtained by considering the parity function \(\oplus_n \colon \{0,1\}^n \to \{0,1\}\) that returns 1 if and only if an odd number of its inputs have the value 1. In the Boolean circuits lecture, we saw that if we had a parity gate, we could compute \(\oplus_n\) with a formula with leaf-size \(n\):

Converting this formula into a formula with only \(\wedge\) and \(\vee\) gates, however, is not nearly as straightforward as was the case with circuits. Indeed, the formula for the parity on 2 bits has leaf-size 4:

As a result, if we replace the \(\oplus\) gates in the original circuit with the formula that computes it on a level-by-level, we see that we double the leaf-size of the resulting formula at each level. With \(n=4\), for example, we end up with the final formula

More generally, this construction gives a formula of size \(n^2\), showing that \(L(\oplus_n) \le n^2\) is at most quadratic. Is this bound tight? Or could it be that there is a formula with linear leaf-size that computes the parity function? To answer these questions, we need to develop methods for proving non-trivial lower bounds on the size of formulas.

Restriction Method

The restriction method is an elegant and powerful method for proving lower bounds in formula and circuit complexity that was originally introduced by Subbotovskaya to prove a superlinear lower bound on the formula complexity of the parity function.

Theorem 1. \(L(\oplus_n) \ge n^{1.5}\).

The starting point of the proof of this theorem and the restriction method itself is a basic observation: for any function \(f \colon \{0,1\}^n \to \{0,1\}\), if we fix any of its input variables \(x_i\) to some constant value \(c \in \{0,1\}\), we obtain a restricted function \(f' \colon \{0,1\}^{n-1} \to \{0,1\}\) on \(n-1\) input variables. Namely, the resulting function \(f'\) is defined by

\[f'(x_1,x_2,\ldots,x_n) = f(x_1,\ldots,x_{i-1},c,x_i,\ldots,x_n).\]The key insight behind the restriction method is that we can compare the formula sizes of \(f\) and of its restriction \(f'\). In particular, for any Boolean formula \(F\) that computes \(f\), there is an index \(i \in [n]\) and a constant \(c \in \{0,1\}\) for which the corresponding restricted function \(f'\) can be computed by a notably smaller formula.

Lemma 2. For any \(f \colon \{0,1\}^n \to \{0,1\}\), there exists \(i \in [n]\) and \(c \in \{0,1\}\) such that the restricted function \(f'\) obtained by fixing \(x_i = c\) in \(f\) can be computed by a formula \(F'\) of leaf-size

\[L(F') \le \left(1-\frac1n\right)^{3/2} L(F).\]

Proof. Since \(F\) has \(L(F)\) leaves and each of these leaves is associated with one of the \(n\) variables \(x_1,\ldots,x_n\), there must exist an index \(i \in [n]\) for which at least \(L(F)/n\) leaves of \(F\) are labelled with \(x_i\) or \(\neg x_i\). Fix \(i\) to be such an index.

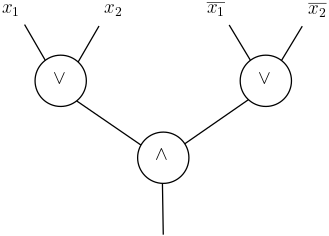

For each gate that takes in \(x_i\) or \(\neg x_i\) as one of its input, there is a value \(c \in \{0,1\}\) for which setting \(x_i = c\) eliminates the gate, in the sense that it will output the same value regardless of the value of its other input. For example, if \(x_i\) is one of the inputs to a \(\wedge\) gate and we set \(x_i = 0\), then regardless of the value of the other input, the gate will always output \(0\).

Without loss of generality, each gate that takes in \(x_i\) or \(\neg x_i\) as one of its inputs is the root of a subtree that includes at least one other leaf and that does not have any other instances of \(x_i\) or its negation in any of the other leaves. Therefore, when a gate is eliminated by a restriction \(x_i = c\), we can always remove at least 2 leaves from \(F\) to obtain a formula \(F'\) that computes the restricted function: the leaf for \(x_i\) itself, and at least one other leaf above the eliminated gate.

There are only 2 possible assignments to the variable \(x_i\), so one of them must eliminate at least half of the gates below the \(x_i\) leaves. Then for this restriction the final size of the formula \(F'\) that computes the restricted function \(f'\) has leaf-size bounded above by

\[L(F') \le \left(1 - \frac{3}{2n} \right) L(F) \le \left( 1 - \frac1n \right)^{3/2} L(F).\]

We can now complete the proof of Subbotovskaya’s theorem.

Proof of Theorem 1. Let \(F\) be any Boolean formula that computes the \(\oplus_n\) function.

Applying Lemma 2 to the \(\oplus_n\) function, we get a function \(f^{(1)} \colon \{0,1\}^{n-1} \to \{0,1\}\) that can be computed by a formula \(F^{(1)}\) of size

\[L(F^{(1)}) \le \left(1-\frac1n\right)^{3/2} L(F) = \left( \frac{n-1}{n} \right)^{3/2} L(F).\]Apply Lemma 2 to the function \(f^{(1)}\), and we get a function \(f^{(2)}\) on \(n-2\) bits that can be computed by a formula \(F^{(2)}\) of size

\[L(F^{(2)}) \le \left(1 - \frac1{n-1}\right)^{3/2} L(F^{(1)}) \le \left( \frac{n-2}{n-1} \cdot \frac{n-1}n \right)^{3/2} L(F).\]Continuing to repeatedly apply Lemma 2, we similarly obtain functions \(f^{(3)},\ldots,f^{(n-1)}\) computable by Boolean formulas \(F^{(3)},\ldots,F^{(n-1)}\) where

\[L(F^{(n-1)}) \le \left( \frac12 \cdot \frac23 \cdots \frac{n-2}{n-1} \cdot \frac{n-1}{n} \right)^{3/2} L(F) = \frac1{n^{3/2}} L(F).\]But applying any restrictions to \(n-1\) variables of the \(\oplus_n\) function yields a restricted function $f^{(n-1)}$ that is either \(x_j\) or \(\overline{x_j}\) for some index \(j\). Therefore, any formula \(F^{(n-1)}\) computing \(f^{(n-1)}\) has leaf-size at least 1. So we have

\[1 \le L(F^{(n-1)}) \le \frac{L(F)}{n^{3/2}},\]and multiplying both sides of this inequality by \(n^{3/2}\) completes the proof of the theorem.

Eric Blais ©2024 — Last edited on Feb. 12, 2024