8. Boolean Circuits

We can approach the task of determining what computers can do from a very different angle by considering Boolean circuits instead of Turing machines.

Introduction to Circuits

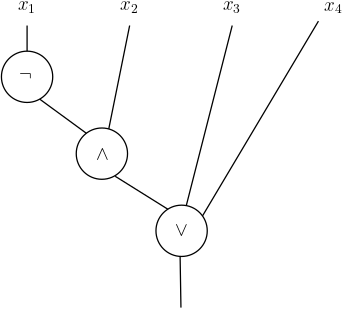

A Boolean circuit (with unbounded fan-in over the standard basis) consists of \(n\) input bits labelled \(x_1,\ldots, x_n\) as well as a sequence of gates \(g_1,g_2,\ldots,g_m\). There are three types of gates:

- NOT gates (also known as negations and denoted with \(\neg\)) take in one input bit and negate it to form their output.

- AND gates (conjunctions, denoted with \(\wedge\)) take in any number of input bits and output 1 if and only if all the input bits have the value 1.

- OR gates (disjunctions, denoted with \(\vee\)) take in any number of input bits and output 1 if and only if at least one of the input bits have the value 1.

The inputs to the gate \(g_k\) are either one of the input bits to the graph or the output of one of the earlier gates \(g_1,\ldots,g_{k-1}\). The output of the circuit is the output of the gate \(g_k\).

There are two important complexity measures for Boolean circuits. The size of a circuit is the total number of AND and OR gates that it contains. And the depth of a circuit is the number of AND and OR gates in the longest path from any input bit to the output of the circuit.

Boolean circuits can be represented with directed acyclic graphs as in this example:

One important note: since the number of input bits to a Boolean circuit is fixed, it computes a Boolean function \(f \colon \{0,1\}^n \to \{0,1\}\). Recall that a language \(L \subseteq \{0,1\}^*\) can be expressed as a family of Boolean functions \(\{f_n\}_{n \ge 0}\) where each \(f_n \colon \{0,1\}^n \to \{0,1\}\) satisfies \(f_n^{-1}(1) = L \cap \{0,1\}^n\). This means that a single circuit in general cannot compute a language, but a family of circuits \(\{C_n\}_{n \ge 0}\) does. Because we have different circuits for different input lengths (in contrast to the Turing machine model, where we have a single machine that must handle all input lengths), circuits are known as a non-uniform model of computation.

First Examples

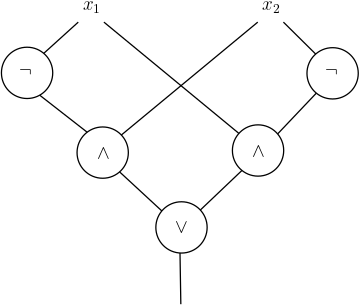

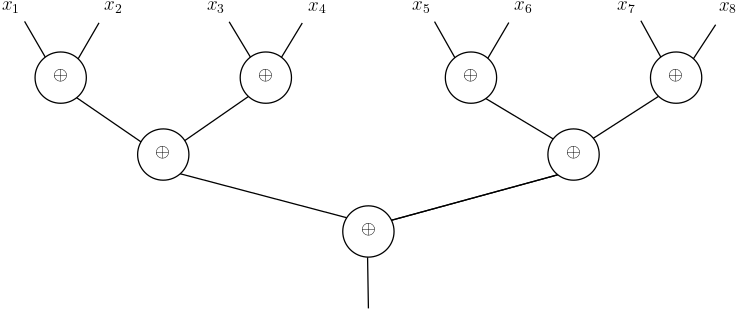

The parity of a set of bits is the function \(\oplus_n \colon \{0,1\}^n \to \{0,1\}\) defined by

\[\oplus_n(x_1,\ldots,x_n) = \sum_{i=1}^n x_i \pmod{2}\]that outputs \(1\) if and only if \(x\) contains an odd number of \(1\)s.

Constructing a Boolean circuit that computes the parity \(\oplus_2\) of 2 bits is a simple task:

Similarly, we can compute \(\oplus_n\) for general values of \(n\) using a circuit with size \(O(n)\) and depth \(O(\log n)\). First, we observe that if we had a parity gate that computed the parity of 2 bits, we could use this gate to compute the parity of a larger number of bits in this way:

Then we can complete the construction of the Boolean circuit by replacing each of the parity-of-two-bits gate with the earlier Boolean circuit we designed to compute this function.

For a more challenging task, see if you can construct a Boolean circuit to compute the majority function \(\mathrm{Maj}_n \colon \{0,1\}^n \to \{0,1\}\) defined by

\[\mathrm{Maj}_n(x) = \mathbf{1}\left[ \sum_{i=1}^n x_i \ge n/2 \right]\]that outputs \(1\) if and only if at least half of the input bits have the value \(1\).

Shannon’s Theorem

One basic property of Boolean circuits that stands in stark contrast to Turing machines is that they are universal, in the sense that they can compute every function.

Theorem 1. For every function \(f \colon \{0,1\}^n \to \{0,1\}\), there exists a Boolean circuit \(C\) of size at most \(2^n + 1\) that computes \(f\).

Proof. Notice that every Boolean function \(f\) can be represented as a table of truth values. For example, the majority function on \(3\) bits can be represented as

\(x_1\) \(x_2\) \(x_3\) \(\mathrm{Maj}_3(x)\) 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 Consider now the circuit obtained in the following way. We start by adding a NOT gate connected to each input. This enables us to have access to the \(n\) literals \(x_1\), \(\neg x_1\), \(x_2\), \(\neg x_2\), … We then create one AND gate for each row with function value \(1\) in the table, with \(n\) inputs corresponding to the \(n\) literals in that row. For example, the first AND gate for the table above is connected to the literals \(\neg x_1\), \(x_2\), and \(x_3\). We then connect all the AND gates with a single OR gate to produce the output of the circuit.

By construction, the circuit outputs \(1\) if and only if the inputs to the circuit belong to one of the \(1\)-valued rows in the table, so it computes \(f\). And the circuit has a total of \(n\) NOT gates, at most \(2^n\) AND gates, and a single OR gate.

This result immediately implies that every language can be computed by a circuit family.

Corollary. For every language \(L \subseteq \{0,1\}^*\), there exists a family of circuits \(\{C_n\}_{n \ge 0}\) that computes \(L\).

Note that the corollary applies even to undecidable languages. So there is no (interesting) analogue of computability theory for Boolean circuits. But we can still consider the complexity of Boolean circuits by asking the next natural question: can every Boolean function be computed by a small circuit? In particular, can every Boolean function on \(n\) bits be computed by a circuit of size polynomial in \(n\)?

As Claude Shannon first showed, the answer to the last question is no. There are functions that cannot be computed by circuits of subexponential size.

Shannon’s Theorem. For every \(n \ge 4\), there exists a function \(f \colon \{0,1\}^n \to \{0,1\}\) that cannot be computed by any Boolean circuit of size \(2^{n/2}/4\).

Proof. We use a counting argument that combines two basic observations.

First, note that that there are \(2^{2^n}\) distinct Boolean functions on \(n\) bits. (The function \(f\) can take \(2\) different values on each of its \(|\{0,1\}^n| = 2^n\) possible inputs.)

Second, we want to give an upper bound on the number of Boolean circuits on \(n\) bits that contain \(m\) AND and NOT gates. There are 2 ways to choose the type of a gate (AND or OR). The inputs to each of these gates are a subset of (i) the input bits, (ii) the outputs of other gates, or (iii) the negation of one of the input bits or the output of another gate. So in total there are less than \(2^{2(n+m)}\) ways to select the inputs of each gate. So the total number of distinct circuits is less than \(\left( 2 \cdot 2^{2(m+n)} \right)^m = 2^{2m(m+n)}.\) When \(m = 2^{n/2}/4\) and \(n \ge 12\), this last expression is at most \(2^{4m^2} = 2^{2^n}\).

So the total number of distinct circuits of size at most \(2^{n/2}/4\) is strictly smaller than the total number of Boolean functions on \(n\) bits. This means that there must be some Boolean function not computable by circuits of this size.

Note that the proof of Shannon’s Theorem implies even more. Namely, it shows that almost every Boolean function (or, more precisely, a \(1-o(1)\) fraction of all Boolean functions) can’t be computed by polynomial-size Boolean circuits. But, amazingly, no one has been able to explicitly identify even a single one of these hard Boolean functions.

Eric Blais ©2024 — Last edited on Feb. 2, 2024