`I'm going to have to start my Fourth of July celebration this year in a Magistrate's Court.

I was arrested yesterday. My crime was to try to take a snapshot of the Liberty Bell.

In this birthplace of American liberty, in the year of our independence the 166th, a citizen isn't permitted to photograph the bell that once proclaimed "liberty throughout the land unto all the inhabitants thereof."

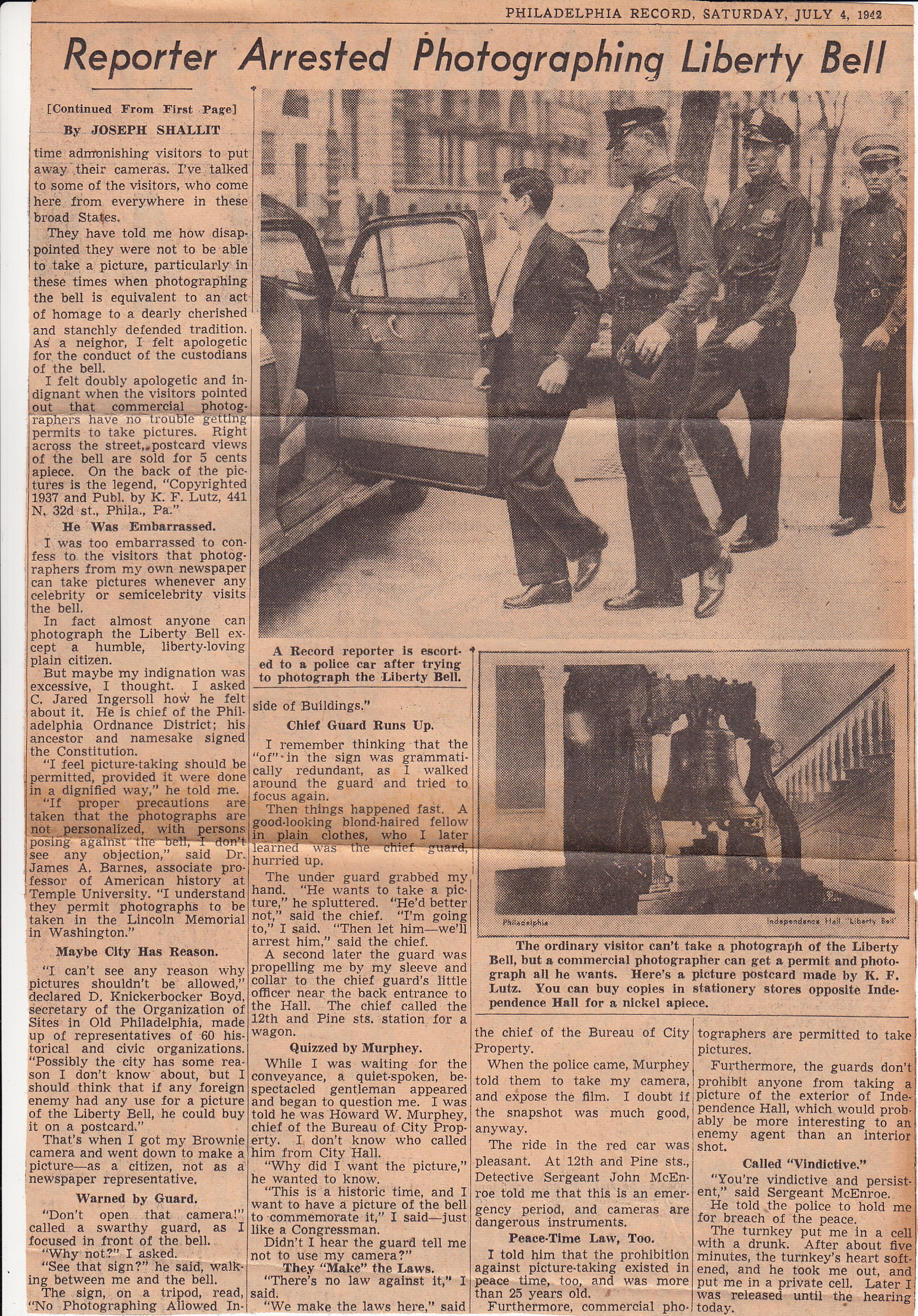

And when I insisted that the prohibition was not in accordance with the great traditions of the bell and Independence Hall, and I clicked my shutter, a guard grabbed me by the collar, dragged me aside, and sent for the police.

I was taken to the 12th and Pine sts. station, questioned by a detective, slated for "breach of the peace," and put in a cell after my necktie was taken away, presumably in fear of suicide.

"The most impudent fellow I've ever had to put up with," growled the guard.

"Are you a Communist?" demanded Howard W. Murphey, chief of the Bureau of City Property.

"Charges could be brought against you that could send you up for 10 years!" declared Detective Sergeant John McEnroe.

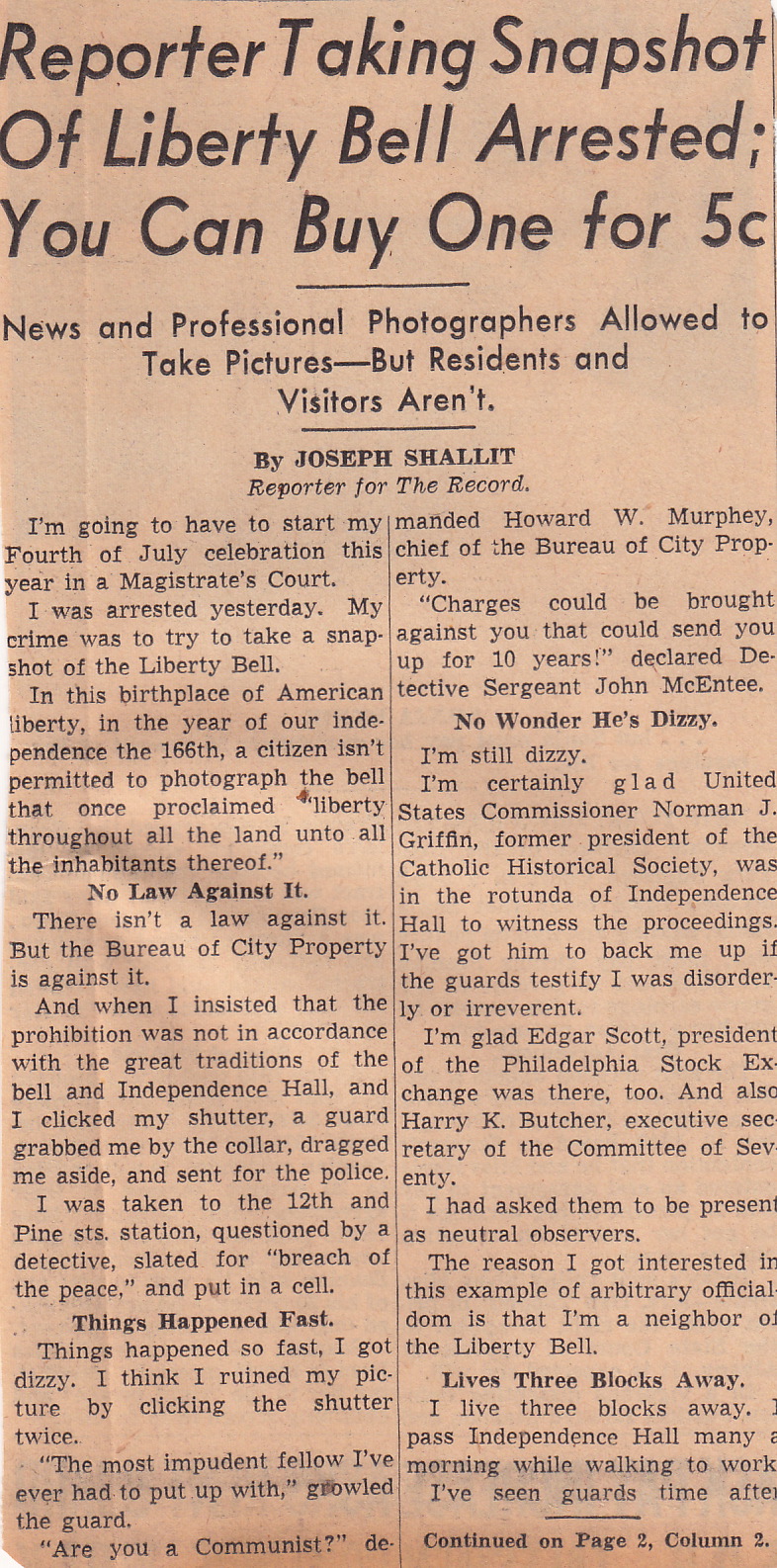

I'm certainly glad United States Commissioner Norman J. Griffin, former president of the Catholic Historical Society, was in the rotunda of Independence Hall to witness the proceedings. I think he'll back me up if the guards testify I was disorderly or irreverent.

I'm glad Edgar Scott, president of the Philadelphia Stock Exchange, was there, too. And also Harry K. Butcher, executive secretary of the Committee of Seventy.

I had asked them to be present as neutral observers.

The reason I got interested in this example of arbitrary officialdom is that I'm a neighbor of the Liberty Bell.

I live three blocks away. I pass Independence Hall many a morning while walking to work.

I often stop for a visit with the bell that called the good citizens together in 1776 to hear the reading of the document beginning, "When in the course of events..."

I've seen guards time after time admonishing visitors to put away their cameras. I've talked to some of the visitors, who come here from everywhere in these broad States.

They have told me how disappointed they were not to be able to take a picture, particularly in these times when photographing the bell is equivalent to an act of homage to a dearly cherished and stanchly defended tradition. As a neighbor, I felt apologetic for the conduct of the custodians of the bell.

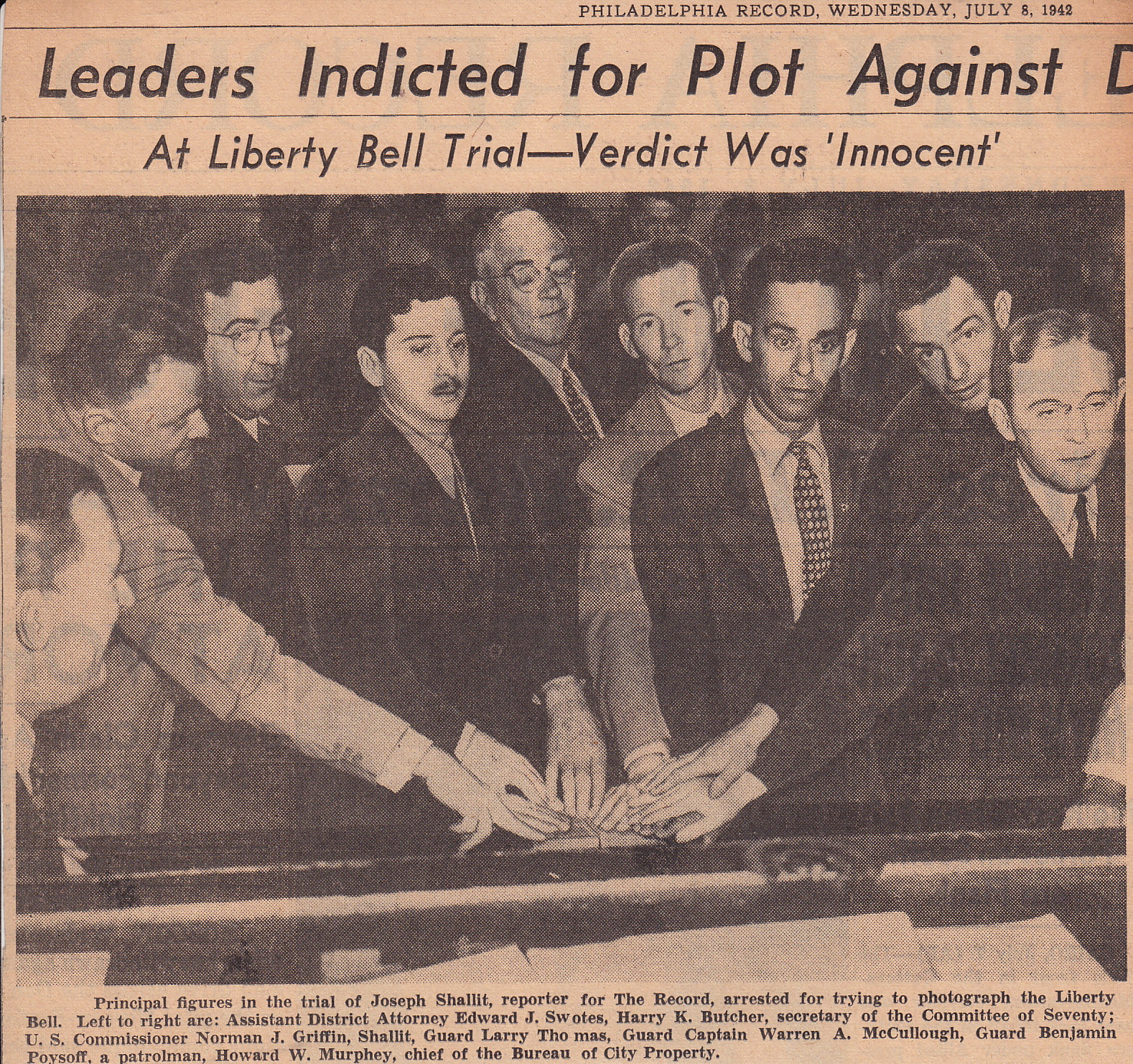

I felt doubly apologetic and indignant when the visitors pointed out that commercial photographers have no trouble getting permits to take pictures. Right across the street, postcard views of the bell are sold for 5 cents apiece. On the back of the pictures is the legend, "Copyrighted 1937 and Publ. by K. F. Lutz, 441 N. 32nd st., Phila., Pa."

In fact almost anyone can photograph the Liberty Bell except a humble, liberty-loving plain citizen.

But maybe my indignation was excessive, I thought. I asked C. Jared Ingersoll how he felt about it. He is chief of the Philadelphia Ordnance District; his ancestor and namesake signed the Constitution.

"I feel picture taking should be permitted, provided it were done in a dignified way," he told me.

"If proper precautions are taken that the photographs are not personalized with persons posing against the bell, I don't see any objection," said Dr. James A. Barnes, associate professor of American history at Temple University. "I understand they permit photographs to be taken in the Lincoln Memorial in Washington."

That's when I got my Brownie camera and went down to make a picture --- as a citizen, not as a newspaper representative.

"Why not?" I asked.

"See that sign?" he said, walking between me and the bell.

The sign, on a tripod, read, "No Photographing Allowed Inside of Buildings."

Then things happened fast. A good-looking blond-haired fellow in plain clothes, who I later learned was the chief guard, hurried up.

The under guard grabbed my hand. "He wants to take a picture," he spluttered. "He'd better not," said the chief. "I'm going to," I said. "Then let him --- we'll arrest him," said the chief.

A second later the guard was propelling me by my sleeve and collar to the chief guard's little office near the back entrance to the Hall. The chief called the 12th and Pine sts. station for a wagon.

"Why did you want the picture?" he wanted to know.

"This is a historic time, and I want to have a picture of the bell to commemorate it," I said --- just like a Congressman.

Didn't I hear the guard tell me not to use my camera?

"There's no law against it," I said.

"We make the laws here," said the chief of the Bureau of City Property.

When the police came, Murphey told them to take my camera and expose the film. I doubt if the snapshot was much good, anyway.

The ride in the red car was pleasant. At 12th and Pine sts., McEnroe told me that this is an emergency period, and cameras are dangerous instruments.

Furthermore, commercial photographers are permitted to take pictures.

Furthermore, the guards don't prohibit anyone from taking a picture of the exterior of Independence Hall, which would probably be more interesting to an enemy agent than an interior shot.

He told the police to hold me for breach of the peace.

The turnkey put me in a cell with a drunk. After about five minutes, the turnkey's heart softened, and he took me out and put me in a private cell. Later, I was released until the hearing today.'