Many will now disagree with this advice. Perhaps it is reader bias since I have only been reading books which recommend this line of investing. I have recently stumbled upon Contrarian Investments and The Uncommon Investor which aim to do things differently. I am yet to read those books.

I have not yet completed the sequel (Wealthy Barber Returns) and I am very curious to find out whether the author is still sticking to active-managed mutual funds as opposed to index-funds. Since the intent here is to write notes on overall financial planning and not a guide to long-term investing, I will just make the note that, low MER index funds that simply track known indices (and therefore invest in all the stocks in that index) have been shown to do better than MOST actively managed mutual funds. The Millionaire teacher is an excellent book for a much more educated discussion on the topic. If time permits, I will consider summarizing the 3-4 books I have read on long-term investing using indices.

Personally, I have been following the Canadian Couch Potato strategy using TD e-series mutual funds (the ETF-based strategy was too new and TD charges commission on those ETFs whereas the e-series are free). An alternate approach these days is to buy "all in one" ETFs. There are for example VBAL, VGRO and VEQT by Vanguard and their corresponding equivalents XBAL, XGRO and XEQT by iShares. The difference is the amount of allocation to equity vs. bonds. My e-series allocation corresponds to VGRO/XGRO, i.e., 80% equity and 20% bonds.

Indices provide a decent return. You will not hit gold but IN THE LONG RUN, you can expect a return between 7-10% depending on the index. Of course there will be times when the market is horribly down, but the market always grows in the long run. This does make it absolutely crucial to realize that this 10% savings account is not money that you should be planning to use in the short-term. We are looking at a horizon for 10+ years at least.

So, once we agree that in the long run, markets go up, we can see how this approach can generate returns. However, the real reason that long-term investing can net you a very nice pile of money in the end is, COMPOUNDING. I would just reproduce the examples from the Wealthy Barber that show how contributing a small amount, say $100 every month, for a long duration, say 30 years, can result in mind-blowing results. Unfortunately, since the book was written 30 years ago, the book uses a return of 15% which, given the current climate (2020), is improbable; current HISA rates are at most 2% if you find an awesome deal, mortgage rates are in the range of 1.5% for a 5 year fixed term and HSBC just offered a rate of 0.99% for insured mortgages.

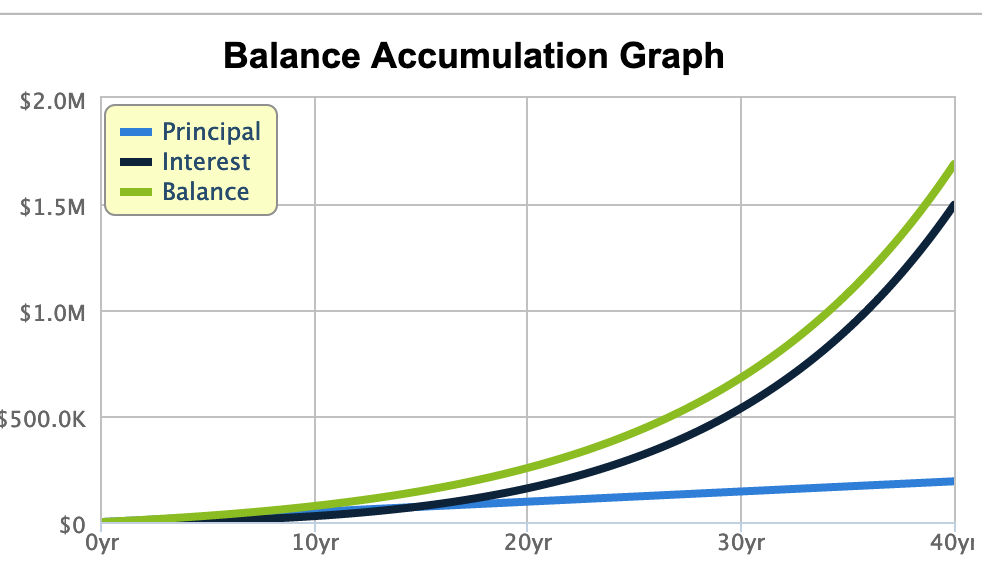

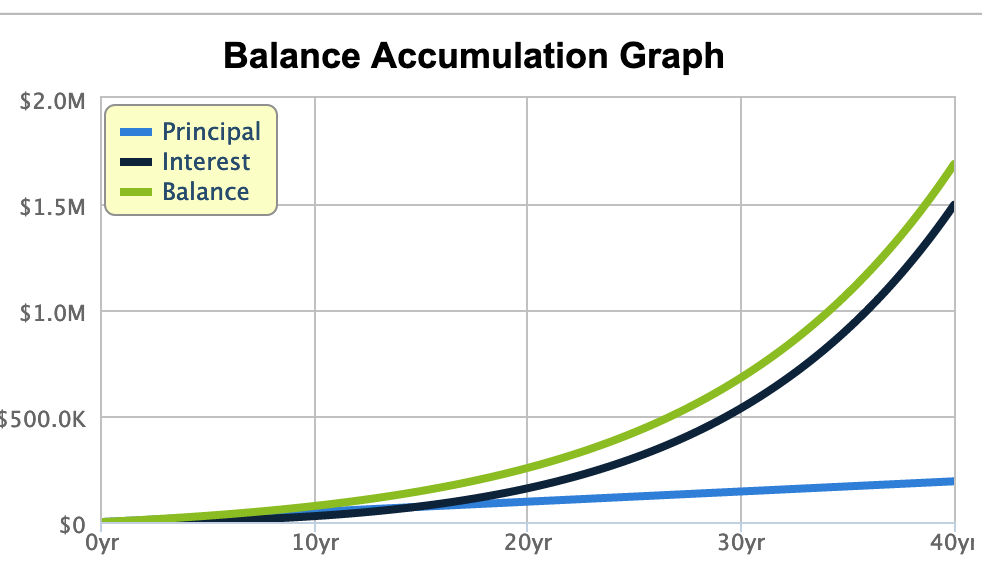

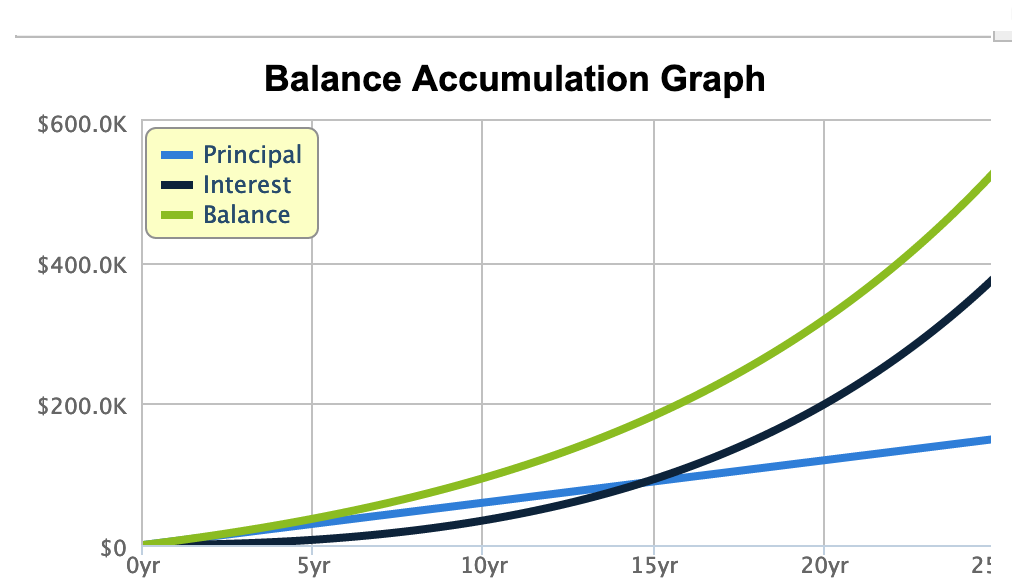

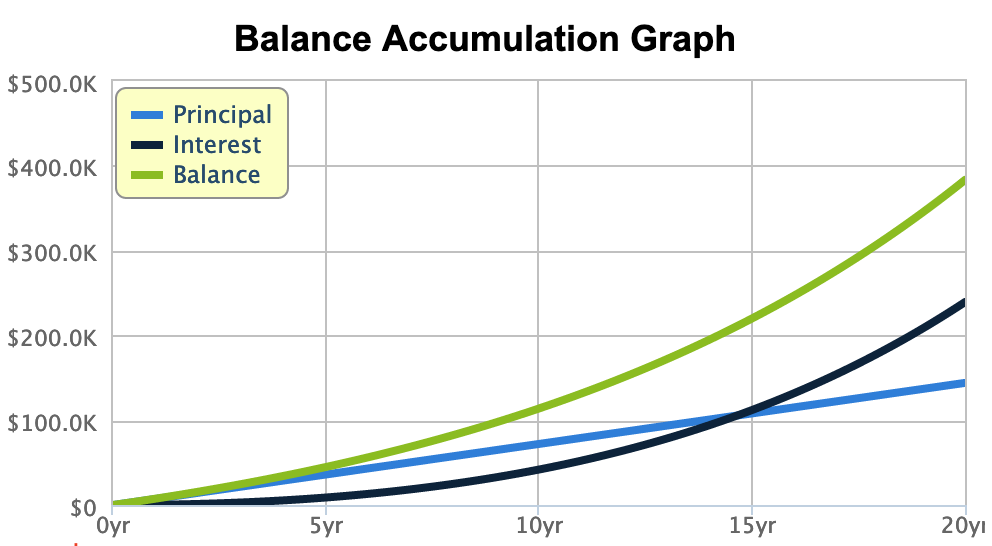

However, once again, even though 15% rates are improbable, the conclusion is still accurate. I wanted to look at the returns for a more realistic 9% return. I chose 9% as that is supposedly the return you can expect from the S&P 500 in a long-term investment (In hindsight, perhaps I should have used a conservative 7% return). Using a compund interest rate calculator I found off the web, I created the following charts:

On the left above, is what happens if you contribute $400 monthly for 40 years at 9% returns. You end up with an amount of $1,688,000. On the right above you accumulate JUST $681,000 if you contribute the same amount of $400 monthly for 30 years at 9%. Note that the only difference is that we have contributed for 10 years less. So, we contributed about $50K less but the loss of 10 years of compunding, reduced our final pot of money by over a million dollars! The lesson: start as early as possible to get the true benefit of compounding!

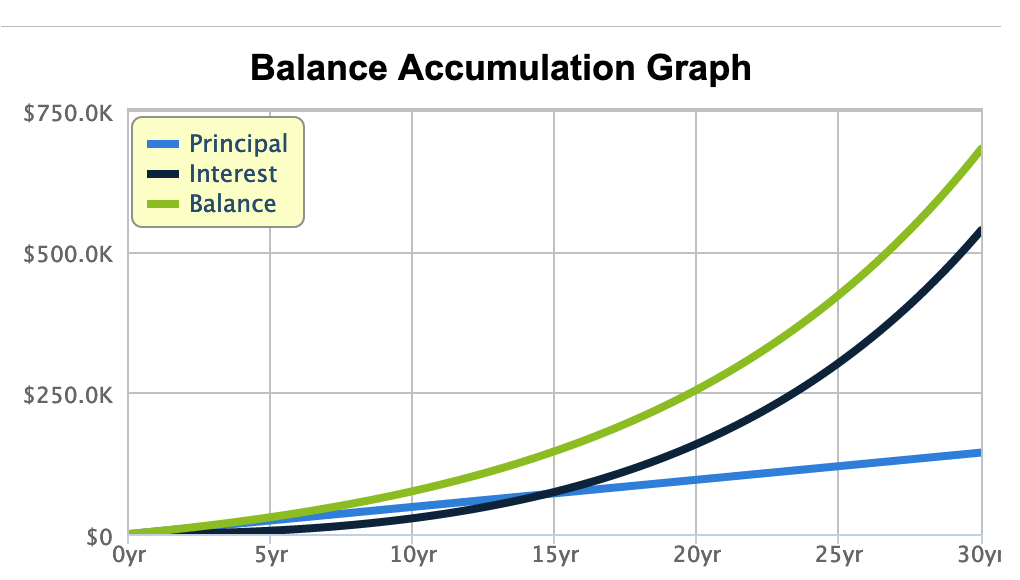

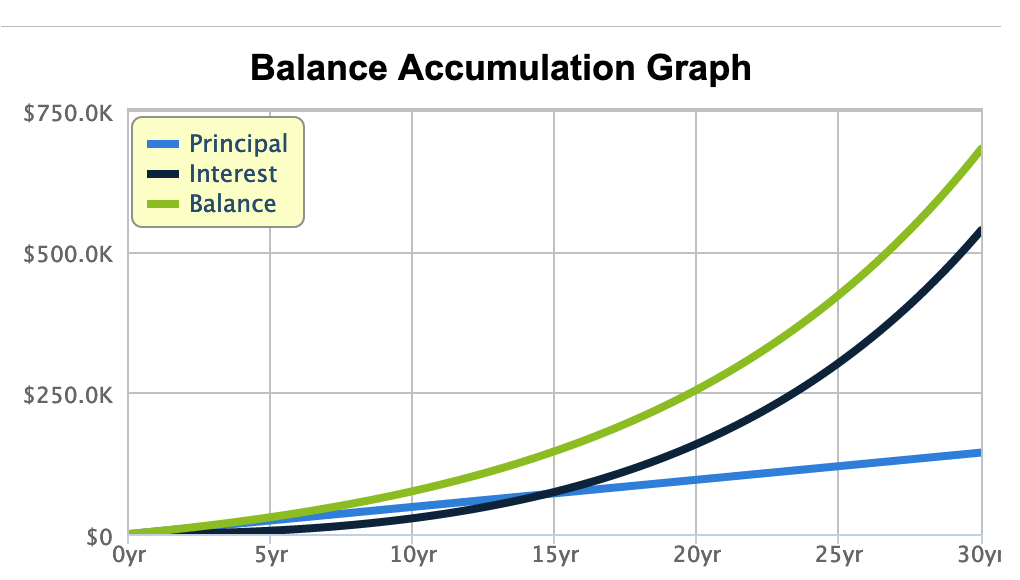

Below to the left is what happens to your money if you up your contribution to $500 monthly for 25 years at 9%. Notice we have upped the contribution but are saving for just 25 years (say you are a 40 year old like I am and want to save until you retire at 65). This will result in a total pot of $529,000. I find this calculation interesting since $500 a month ($6000 a year) represents the current contribution room in a TFSA (which I discuss below). So technically speaking, if the contribution room was to never increase (it is supposed to be indexed to inflation), if we were to contribute this amount yearly in our TFSA, in 25 years we would net $529,000 tax free in our TFSA. The last graph, below to the right, is what you can do if you are running late with your savings. I used a monthly contribution of $600, saved for 20 years at 9%. This nets a total of $383,000.

Of course, the above calculations used a 9% return and as I mentioned earlier, there is no guarantee. Online reading tells me that assuming a 6-7% rate makes more sense, especially since you are likely not going to invest all your money into a 100% equity fund (especially as you get older). The point here was to demonstrate compounding at a currently possible return.

The Govt. Of Canada announced the creation of TFSAs in 2008. It is a great benefit for people who want to save money though unfortunately the Government messed up on the name. It should have been named TFIA, Tax-Free Investment Account, or TFSP, Tax-Free Saving Plan (similar to RRSP which I discuss later in the retirements saving section). The reason many consider this a screw up is because for the longest time, and even now, many Canadians assume that a TFSA is just an account similar to a High-Interest Saving Account (HISA) where you put in your money and you get some measly guaranteed return. That is totally not it. You can hold all sorts of investments such as stocks, bonds, mutual funds, ETFs, GICs and yes cash earning interest, in a TFSA.

The main reason why this account is awesome is due to it being a tax-free account; not a tax-deferred account where your withdrawals are taxed, but a true honest to goodness tax-free account. You get to deposit post-tax money, i.e., money on which tax has already been deducted. But from then on any earnings in the form of capital gains, dividends or interest is not and will not be ever taxed. Yes, it is indeed a shining star in a country where often it feels like you must pay tax on everything (As an aside, the most shocking thing for me was when I found out that when you buy a new house you must pay the full HST on it. ARE YOU KIDDING ME!, is literally what I said. Luckily, I then found out that there are rebates available that reduce the HST depending on whether you will reside in this new house or rent it out. But still imagine 13% HST on a half a million dollar house!). That said, I am actually okay with the high tax rate in Canada but that is a story for another day.

Of course there are rules for the TFSA, otherwise everyone would be piling in all their savings into TFSAs. You only get to deposit a fairly low amount each year. Currently, the amount stands at $6K but will be increased based on inflation. There are also some rules regarding who can open a TFSA. In short, you become eligible to maintain a TFSA if you are 18+ (perhaps 19+ in some provinces) and are a resident of Canada. If you are not eligible or you over contribute, there is a 1% penalty per month. Oh and yeah, contribution amounts accrue in that if in one year when you were eligible you did not contribute, you carry forward that contribution room to the next year. While your CRA account will tell you how much contribution room you have (I believe the amount is updated end of February or beginning of March as that is the deadline given to the banks to report contributions to TFSAs to the government), I recommend keeping track of the contributions yourself. If you were and have been eligible for a TFSA since its inception, but have never contributed to a TFSA, your contribution room for 2020 is/was $69,500 (because we had one interesting year where the contribution room was $10,000).

Here is the next big advantage of a TFSA. You can withdraw money any time. There are no rules or regulations to follow and remember, there is no tax payable. Not only that, any withdrawal you make creates an equivalent contribution room in your account in the following calendar year. This is important to remember. Say you have a maxed out TFSA and you retrieve 5000 in 2020. You cannot contribute anything back in 2020 even though you withdrew 5000. However, come 2021, your contribution room is now 5000 plus the 2021 amount of 6000. Also note that the withdrawal and the subsequent contribution room it creates has nothing to do with how much you had initially contributed. Say you have 0 contribution room in your TFSA but have done really well, accummulating a balance of $100K in the account. You can withdraw all of it and have that contribution room available the following year. Notice that even though the maximum allowed contribution room so far is 69,500, you would have a contribution room of $100K since that is what you withdrew!

In case you are wondering why I decided to talk about TFSAs at this point, personally, I think this account is ideal for investing the 10% savings. If your 10% comes to $500 a month, then this will nicely fit the current $6,000 limit (remember this will increase based on inflation). We looked at what would happen if we invested 6000 a year at 9% for 25 years; we end up with over half a million dollars. Of course, if your take home is more, you could put the rest in a non-sheltered account.

Not all TFSA accounts are created equal. Depending on your brokerage, they might charge different fees. There is intense ongoing competition between brokerages and fees have been coming down. There are many who no longer even have a minimum portfolio amount requirement. Also, remember that we are going to be contributing monthly, most likely to an index fund. It would be useful to have access to a wide variety of index funds and also not to have to pay excessive fees when buying (fees at selling is okay because we are going to buy and hold!).

To be honest, I still haven't made up my mind about this. I do not understand why the author talked about the 10% savings first; shouldn't saving for retirement be more important than aiming to have the ability to buy expensive stuff. Maybe the ordering in the book is irrelevant and he considers all topics equally important.

There is a plethora of material on the web for calculating how much money you will need for retirement. While I am yet to seriously calculate my retirement number (monthly funds required for a comfortable living), the author recommends we all do this.

With only some thought given to what I would need during retirement, it makes me think this number is likely not super high and is likely lower than our current monthly expenditure. Some things to consider:

Alright, so given this thought process, we all need to arrive at a yearly amount that we think will be enough for us to live well. But, we have to also account for inflation. The number you came up with is likely assuming present-day prices. Things will certainly cost more when we retire.

Let's say we have now determined the inflation adjusted value X that we need to live comfortably during retirement. We need to figure out how much we should save now so that by the time we retire we will receive X every year. Well, our perssonal savings do not have to net us X yearly. There are government contributions to this retirement amount. I discuss the two main ways the government supports people in their retirement. This is certainly not a detailed set of rules and the reader should certainly look up more details on the appropriate web pages.

The Canada Pension Plan provides a monthly amount to individuals who were employed and contributed to CPP. The earliest you can start receiving the benefit is at age 60 although it can be delayed till as late as age 70. Of course, the later you start taking the benefit, the higher the amount. The maximum CPP amount is 1,175 a momth. If you start taking CPP at 60, the maximum you can get is $8,800 per year.

Any canadian citizen who has resident in Canada for at least 10 years is eligible for at least some amount (the rules are more complex than this simplification!). You become eligible for OAS when you turn 65 and the amount gets bigger the longer you delay. After age 70, there is no benefit of delaying and in fact you can lose some benefits. The OAS amount is based on your yearly income. Between $77k and $128k there is a sliding scale with OAS benefits ceasing if your income is more than 128K. Below $77k, and assuming age 65, your maximum amount is $614. As mentioned earlier, the rules are complex and vary depending on your personal situation.

This is NOT a government plan although public service employees often(always?) have pension plans. Some jobs (teachers, nurses, university faculty etc.) have Defined Pension Plans that are managed by their employer. The idea is simple; a monthly amount is deducted from your paycheck before you even receive it, and is contributed to your pension. Notice that this is above the CPP contribution that you must also make. Once you retire, you are guaranteed a certain yearly amount. Pension plans vary in their benefits and therefore it is absolutely crucial that if you do have such a plan, you contact HR and determine what your pension is expected to be at reirement.

We had said that the inflation-adjusted amount we need to live comfortably is X every year. Let's assume that we will get an amount of Y from the two government sources of retirement income every year and our pension. In other words, our personal retirement savings must provide for a yearly amount of X - Y. If this amount is negative, then you are good as you need not save anything extra for your retirement. However, if the amount is positive, that is the amount we need to personally (outside even our pension plan) save for.

One interesting concept is the ideal scenario where you save enough money in your retirement pot so that it can generate X-Y indefinitely. Note that this is indeed a utopian scenario where your retirement pot stays preserved and you just live off the returns.

Curious about how this would work out, I created a scenario, with the following assumptions:

This means that the amount my retirement pot needs to generate each year is X - Y = 60,000 - (8,700+7,300) = 44,000. The question I asked is, how much money do I need to save up till I am 65, so that it can generate $44K yearly. (Note that while we could have a scenario where we start at 60 with CPP, there is a period 60-65 years of age where you do not get OAS. To keep things simple, I chose the 65 retirement age).

An important consideration has to be where this pot of money will be invested to ensure the return rate I am hoping for. While equity stock indices have over the long term given 7+ % returns, they can fluctuate drastically in the short term. That is not where you want your retirement savings close to or during retirement. I chose a return rate of 5% which is realistic though perhaps on the slightly high side if you think of a 40% equity and 60% bond allocation of the money given the low prevailing interest rates right now.

Keeping the math simple, one needs $900K returning 5% to generate a $45K yearly revenue. Of course this money will be taxed. NEVER FORGET TAXES AND INFLATION!

While we are working with inflation-adjusted numbers, we did not address taxes. So, let's add tax into the mix. CPP is taxable income. OAS is technically taxable income but only if your net income goes above $77k (which will not be the case in this scenario). Income from Pension and withdrawals from RRSP (look below for details on this account) are also taxed. For simplicity sake, let's ignore the tax on CPP, and just compute the amount needed that will net us 44k, post-tax. In Ontario, if you earn $60K, tax will be $14,500 (effective rate of 24.12%) netting $45,527. So in other words, our retirement pool must generate $60K yearly so that after taxes we are left with the $44K we needed for our X-Y amount. At a 5% return, you need to have a savings of $1,200,000 to generate $60K without eating into your retirement fund.

I do not know about you, but the thought of needing to save 1.2 million by the age of 65 frightens me. There are however something to keep in mind.

As a last thought experiment, let's look at some numbers in terms of how much we should be saving to make it to the 1.2 million end goal. We will use the more conservative 7% figure for our rate of return from whichever index tracking fund we are invested in. We will change the number of years we are going to save and see what effect it has on the amount we must deposit each month

The government wants you to save for retirement (they likely realize that CPP and OAS amounts are not nearly enough to live on and fewer and fewer people in Canada have access to a Defined Pension Plan). To encourage savings, the government has made available RRSP accounts. We discuss the highlights of these accounts without getting stuck in the weeds (and trust me there are a lot of weeds!).

If you are earning, you have an RRSP contribution amount. The current year's amount is the lesser of 18% of your earned income from the previous year and the RRSP limit for that year ($26,500 for 2019). Your overall contribution limit for a year is the sum of the current year's contribution amount added to any unused amounts from your previous years of contribution room. (There are a few other details such as if you are contributing to a Defined Pension Plan that contribution is deducted from your contribution room). The Canada Revenue Agency provides the RRSP deduction limit in your Notice of Assessment each tax year.

The key advantage of an RRSP account is that it is a tax-deferred account. What this means is that any contributions you make to this account are considered pre-tax earnings, i.e., the government has not counted this amount towards your earnings for the year and therefore you will not pay any tax on the amount you contribute to the RRSP. So if you earned $100K and you contributed $10k to your RRSP, come tax time, your annual income will be considered to be $90K on which you will be taxed. Note that this does not mean that you will be never taxed on the $10k you put into your RRSP; it just means that this amount is allowed to grow without tax, until you retire and then withdraw it. At that point, you will be taxed on this money, and any gains/dividends/interest you earned on it, at your current tax rate which is likely going to be less than your current rate as you are retired. I cannot stress the importance of this last part enough. Putting money into your RRSP account only makes sense if you are sure that your tax rate now is higher than the tax rate you will have once you retire. Some people incorrectly use RRSP contributions as a way to get a "tax refund". The idea being that "I will contribute to the RRSP and because my company deducted tax from my paycheck without expecting this, I will get a tax refund". Yes you will get a tax refund but you are just delaying the tax. It comes down to what you do with the tax refund. Do not waste that refund, deposit it in your RRSP as well to offset the tax that you will eventually need to pay. Also, if you are currently in a lower tax bracket, it does not really make sense to contribute to the RRSP. Since RRSP contribution rooms accrue, it might be better to pay the tax now and place this amount in a non RRSP account. Once your tax rate rises, then you can use this additional contribution room. Also, once again: if you expect your tax rate to be higher at retirement than what it is now, it makes no financial sense to invest in an RRSP. You are better of investing in a non-sheltered account (TFSA is obviously ideal).

Another type of RRSP account, is a GRRSP, Group Registered Retirement Saving Plan, an RRSP account that is managed as a group by your employer. This type of account can actually have a number of disadvantages; higher MERs (Management Expense Ratios) and restricted investment options. However, there is often one advantage which overshadows all disadvantages. Your company might offer to match your contributions to the GRRSP to a certain amount. For example, the company might say they will match any contribution up to 5% of your income. That is free money! Always take free money!

You can hold multiple RRSP accounts. In fact, many individuals who have a GRRSP choose to contribute only up to the amount for which their employer will also contribute. They then open a separate, more flexible account which allows them access to better investment options with lower MERs.

Alright, that sounds great but there are some disadvantages to contributing to an RRSP account. The biggest being that the money is locked in to that account. Well not technically locked; it is still yours and you can access it but it will come at a cost. Remember, the money in the RRSP is pre-tax. So, if you withdraw it, you owe tax on it. The amount withdrawan from an RRSP pre-retirement gets added to your income and you are taxed at your applicable marginal tax rate. Not only that, but there is actually a withholding tax, i.e., because there will be tax due on the money you withdraw, the bank will withhold some percentage of the withdrawal right away. The amount withheld depends on the amount withdrawan. You say fine. I will still withdraw after all I have to pay tax at some point. There is another disadvantage; you lose the contribution room that you had, i.e., unlike a withdrawal from a TFSA where you get an equivalent contribution amount added in the next calendar year, any withdrawal from an RRSP causes you to lose that contribution room. Well, not quite. There are two exceptions to when RRSP withdrawals can be useful without incuring tax or loss of contribution room.

First, the RRSP Home Buyers Plan allows eligible first-time homebuyers to withdraw up to $35k tax-free from their RRSP to be used towards a down payment. However, you must return the money back into the RRSP, 1/15th per year; think of it as an interest-free loan to yourself with 15 equal payments over 15 years. Second, the Lifelong Learning Plan allows individuals to retrieve money from their RRSP account for their, or their spouse's, education (not their children's). The Lifelong Learning Plan of course comes with rules (up to $10K withdrawal in a calendar year, maximum of $20K etc.). Also, once again, the withdrawn amounts must be repaid; within 10 years typically 1/10 of the amount withdrawn until the balance is zero.

There is of course a lot more to RRSPs. I encourage everyone to read more about them. Directly from the Govt. of Canada web pages or the hundreds of articles available freely on the web.

Please report any errors, comments or crucial points that I missed to the email address at the top of the page.