We present a new method of modeling ethnographic descriptions. The method draws on recent anthropological and sociological developments in ethnography and receives its technical foundation from production system models in cognitive science. We display models as graphs to show logical relations among events, and we use models as grammars to generate acceptable sequences of concrete and abstract events. We illustrate the approach in a detailed analysis of approach-avoidance play in the peer culture of nursery school children.

In cultural anthropology, collection and interpretation of ethnographic data lead to changes and refinements in the conceptualization of culture and to investigation and evaluation of theoretical views. Over the last twenty years this inseparability of theory and method has led to major developments in theoretical anthropology and to advances in the collection, organization, representation, interpretation, and reporting of ethnographic materials.

Meanwhile ethnographic (or field) research in sociology mainly refers to a type of methodology, to a research tool that is not utilized effectively for theoretical purposes even though it has a long tradition of use in sociology. Great exemplars of sociological ethnography--like the work of Whyte (1955), Becker (1963), Goffman End p. 1 (1961, 1971)--certainly are theoretically rich, but they do not tell us how to focus ethnographic data for sociological presentation or how to articulate ethnographic data with theories of sociological concern.

Given that ethnographic research is our most intensely empirical approach for studying social systems and culture, given the possible gains of heightened concern with ethnography, as demonstrated in anthropology, and given the recent emergence of interest in culture within sociology (see, for example, Becker 1982; Corsaro 1985; DiMaggio 1987; Fine 1987; Swidler 1986; Willis 1981; Wuthnow 1987), we should reconsider the application of ethnographic research in sociology and re-engage the search for truly qualitative methods of analysis that are systematic and disciplined, a search that ended too abruptly with Robinson's (1951) critique of analytic induction.

This paper presents a procedure for modeling events that have been observed in the field. One benefit of the suggested approach is that it focuses ethnographic interpretation on the issue at hand, selecting what must be said from the plethora of what could be said. Another benefit is that it formalizes cultural explanations into empirically grounded logical structures that can be examined and debated by experts, then used by the discipline at large as condensations of ethnographic research.

The new method of qualitative analysis offers systematic, uniform, computer-assisted procedures for data analysis, yet paradoxically it does not lighten the work of ethnographers. Rather, we admit at the outset that the approach adds time-consuming hard work to an ethnographer's burdens because it asks more questions than are usually put to data and it demands extraordinary precision and meticulousness in descriptions of events.

In the next two sections we briefly review recent developments in ethnographic research in cultural anthropology and sociology and outline the new methodology for analyzing ethnographic data. We then illustrate the method by focusing on a routine (a recurrent pattern of behavior) in the peer culture of nursery school children. We begin our analysis with a cultural interpretation of the routine. Then we (1) formulate the structures of events that comprise specific instances of the routine; (2) affirm that these structures with refinements can account for the observed event End p. 2 sequences; (3) reinterpret the significance of the routine for children's peer culture and their acquisition of social knowledge; and (4) abstract a structure to account for multiple, cross-national instances of the routine. We conclude by evaluating the potential of this type of methodology.

As Marcus and Fischer (1986) argue, reactions to the dominance of functionalist ethnography in the 1930s set off a still-evolving concern in cultural anthropology with capturing the native's point of view. This concern is most apparent in the development of ethnoscience, in which culture is defined as the "organizing principles underlying behavior" (Tyler 1969, p. 3). Ethnographers must discover the organizing principles of a culture--the semantic world of the natives--while avoiding the imposition of their own semantic categories on what they perceive.

Another reaction can be seen in the interpretive view of Geertz, who defines culture as "an historically transmitted pattern of meanings embodied in symbols, a system of inherited conceptions expressed in symbolic form by means of which men communicate, perpetuate and develop their knowledge about and attitudes towards life" (1973, p. 89). Culture underlies not competence but rather social performance, which involves the innovative use of competence. In the interpretive approach, culture is a text to be discovered, described, and interpreted.

The cognitive and interpretive views of culture have projected ethnographers working in the two traditions in widely divergent methodological directions. Ethnoscience has become more and more formalistic, placing increasing emphasis on the correct technical strategies of data elicitation and analysis. In contrast, the interpretive approach has come to rely on "thick descriptions" of key routines and rituals of a culture and the interpretive virtuosity of the ethnographer in distilling meaning from such descriptions. Sociolinguistically oriented ethnography represents a middle ground between these two traditions (Briggs 1986; Schieffelin and Ochs 1986).

There are a number of sociological texts that describe field research strategies in sociology (Becker 1970; Denzin 1977; Lofland End p. 3 1971; Schatzman and Strauss 1973). But aside from Glaser and Strauss's (1967) discussion of grounded theory, there have been few systematic attempts to link field research with theory development. Grounded theory is primarily a method of data analysis containing abstract descriptions of techniques (like the constant comparative method) and little discussion of issues of data collection beyond that of theoretical sampling. Although it has generated concepts (Glaser and Strauss 1964) and theoretical statements (Glaser and Strauss 1970), the grounded theory approach rarely involves the microanalysis of actual interactive events or uses cultural informants in data analysis. In fact, data analysis often remains at a very general level, while concepts and theory are described in great detail and selected examples from field notes are used for illustration. This pattern of presenting illustrative cases to support theoretical conclusions rather than linking theory to actual data analysis typifies much of sociological field research (see Fine 1987 for a recent example).

The method we present in this paper draws on critical work (Cicourel 1964) stressing the importance of accountability in field research. Ethnographers can increase such accountability by producing a natural history of decision making in data collection (Becker 1958) and by including cultural informants in data analysis (see Corsaro 1985 for an example). But this paper goes beyond the issue of accountability and addresses the problem of vagueness in data analysis and theory generation in sociological field research by offering a method for systematic analysis of ethnographic data.

Our proposed method uses production-system models. Work on production systems began with Newell and Simon (1972) and has been continued by computer scientists (e.g. Waterman and Hayes-Roth 1978), psychologists (e.g. Anderson 1983), and sociologists (e.g. Fararo and Skvoretz 1984, 1986). Leads provided by Axten and Skvoretz (1980) led to a way of modeling empirical data to interpret how event sequences are assembled by actors (see Heise 1988, 1989 for in-depth discussion).

Our production-system models consist of sets of events that occur in a domain and sets of logical relations that define the End p. 4 prerequisites for some events, plus a few general rules that govern events. The models act as grammars in that they theoretically delineate permissible sequences of action, including the observed event sequences that shaped the models.

Culture enters into definitions of events, and only a culture expert--whether an indigenous consultant or an ethnographer--can provide the event definitions that constitute basic data for formulating a model. Logical relations among events are also manifestations of culture, and these too must be specified by culture experts.

In principle, one could elicit a model directly from an expert by asking what events are relevant to a routine and how they are connected. However, the expert is likely to overlook key aspects of the routine, no matter how persistent the elicitation, because the routine may not be formulated explicitly, only produced interactively. Moreover, the process of defining logical relations systematically is overwhelming when done in the abstract.

Rather, models should be constructed by examining recorded event sequences. Working with actual incidents addresses the problem of defining events: A culture expert examining the record can identify the events that are culturally recognizable and relevant, and those are the events that a model has to deal with in one way or another. Working with real incidents also drastically reduces the burden of defining relations: In particular, the expert is freed from pondering whether later events might be prerequisites for earlier ones. Additionally, sequences of actual events can be analyzed further to shape a model that accounts for reality.

Our proposed method of analysis requires two different kinds of data. First, we need experts' definitions of events and logical relations. Second, we need records of actual event sequences to aid elicitation and to define correct orderings of relevant events (though not necessarily the only permissible orderings).

The production-system approach to modeling events uses several general principles of action, i.e., very simple ideas associated End p. 5 with the notion that events have prerequisites. First, it assumes that an event cannot occur until all of its prerequisites have occurred. The prerequisite events establish certain physical, social, or mental conditions necessary for the occurrence of other events. Second, the approach assumes that occurrence of an event depletes its prerequisites, i.e., that it uses up the conditions that the prerequisites created. This is not always true, but it serves as a useful general rule, and exceptions can be defined as necessary. Third, also as a general rule with exceptions, the production-system approach assumes that an event isn't repeated until the conditions it created are used up by some consequence. The premise is motivational in some cases: It would be redundant and pointless to produce more and more of a condition unless that condition is being utilized. But also, attainment of a condition may preclude further action to produce the same condition.

The action principles become important when we try to use a structure of prerequisites to account for a sequence of events, because the assumptions about the production of action define the sequences of events that are permissible. For example, in principle an event cannot occur before its prerequisites have occurred. If we find an ordering of events in which this rule is violated, then we know that something must be wrong with our model or with our data. In principle, an event cannot repeat unless its prerequisite events have also repeated. Here, too, an ordering of events that violates the principle suggests problems in model or data. In principle an event cannot repeat unless some of its consequences occur between times. If the rule is violated, then once again something must be wrong, something must be changed.

Event structure analysis includes the following steps.

1. Field observations are translated into sequences of elementary events. The events are described in culturally relevant terms by an expert to insure that the underlying cultural logic of the events is incorporated semantically in the descriptions.

2. A logical structure is developed by the culture expert to portray the dependencies among the elementary events. End p. 6

3. The logical structure and added action principles are applied as a grammar to account for actual sequences of events. Changes are made whenever the model cannot account for some particular sequence: The logical structure is modified, the action principles are adjusted, the data are amended, or the episode is reformulated in different terms. Revisions continue until the model fits available data.

We now turn to ethnographic materials to illustrate and elaborate these ideas.

In his research on American and Italian nursery school children, Corsaro (1985, 1988; also see Corsaro and Rizzo 1988) has noted that children are frequently exposed to social knowledge and communicative demands in their everyday activities with adults that raise problems, confusions, and uncertainties. These problems are later reproduced and readdressed in the activities and routines that make up peer culture. In this sense the routines of peer culture offer children opportunities to deal with problems, confusions, and concerns jointly or communally with peers.

Corsaro has identified a large number of routines in the peer culture of nursery school children, but here we will focus on one routine: approach-avoidance. We first present two examples of the routine: a spontaneous version observed in an American nursery school and a more formalized version observed in an Italian nursery school. The first example describes a videotaped enactment of the routine. The second example is from field notes collected by Corsaro (1988). We then interpret the significance of these data for peer culture (see also Corsaro 1985, 1988). Finally, we expand these interpretations by modeling the ethnographic data.

Three children (Beth, Brian, and Mark), who are all around 5 years old, are playing on a rocking boat in the outside yard of a nursery school. After about 10 minutes of rocking, Beth notices End p. 7 another boy (Steven, 6 years old) walking at some distance from the boat with a bucket (a large trash can) over his head.

"Hey, a walking bucket! See the walking bucket," shouts Beth.

Brian and Mark are facing the opposite direction and do not see Steven and are therefore not sure what Beth is talking about.

"What?" says Brian.

"A walking bucket. Look!" Beth points to where Steven is walking with the bucket on his head. Brian and Mark now turn, look, and see Steven.

"Yeah!" says Brian, "Let's get off."

Brian, Mark, and Beth now stop the boat, get off, and with Mark leading the way slowly approach Steven.

When they reach Steven, Mark and Brian push the bucket and start to raise it over Steven's head. Steven responds by beginning to flip the bucket off his head. Brian yells "Whoa!" and the three children, pretending to be afraid of Steven, race back to the rocking boat with Steven pursuing them. Steven runs toward the rocking boat, flailing his arms in a threatening manner. Brian, Mark, and Beth pretend to be afraid, screech, and move to the far side of the boat. Steven stops at the vacant side of the boat and rocks it by pushing down on the boat with his hands. Steven does not actually climb onto the boat, nor does he try to get at the other children.

Steven then returns to the dropped bucket and places it back over his head. Brian, Mark, and Beth watch from the boat, giggling and laughing.

"Let's kick him," says Mark.

Mark and Brian now jump down from the boat and move toward Steven, who still has the bucket over his head. Beth remains behind on the boat. Mark reaches Steven first and kicks at his legs. Although it is difficult to tell from the tape, Mark's kick seems to barely miss Steven's legs. Brian runs up and also kicks at Steven, but he clearly misses. Mark and Brian then run back to the boat just as Steven begins to take the bucket off his head. Steven flips the bucket to the ground and moves toward the boat just as Brian climbs up on the boat with Mark and Beth. At this point another child (Frank) also gets on the boat. Steven takes on a threatening pose, looking at the children on the boat, but does not actually move to the boat. Steven then replaces the bucket on his head and End p. 8 begins walking around the play yard, at first moving away from the four children who are rocking on the boat.

"Whee!" Faster! Faster!" shouts Beth.

Steven is still some distance from the boat but begins to move toward the children.

"Hey, he's coming," yells Beth.

Brian taunts Steven, shouting "Hey, you big poop butt!" All the children laugh, and Beth yells "Hey, you big fat poop butt!"

Steven seems to ignore these taunts and continues to walk around the yard with the bucket over his head. Beth now jumps from the boat and runs toward Steven (the Walking Bucket) with Brian close behind her. Mark and Frank also move toward Steven but are trailing Beth and Brian. As Beth nears Steven she veers off to the left while Brian runs up to Steven and pushes the bucket. Steven begins to take off the bucket just as Mark pushes it, with Frank standing right behind Mark. Brian, Mark, and Frank now flee from Steven, who chases Mark and Brian back to the rocking boat. Frank and Beth do not return to the boat and seem to have gone inside the school. Steven pursues Brian and Mark to the boat and again touches the vacant side, while Brian and Mark are on the opposite side.

Steven then returns to the bucket and replaces it on his head. Once Steven does this, Brian jumps from the boat and moves toward him. Mark does the same and quickly passes Brian. However, this time Steven flips the bucket off his head before Mark pushes it. Brian runs away from Steven and returns to the boat. Meanwhile, Mark runs up to and confronts Steven and they begin to fight. After Mark and Steven struggle for a few minutes, a teacher enters the scene and separates them. At this point Steven and Mark leave the play area and move inside the school and the routine ends.

Cristina, Luisa, and Rosa (all around 4 years old) have been playing for some time in the outside yard near the scuola materna when Rosa points to Cristina and says "She is the witch." Luisa then asks Cristina "Will you be the witch?" and Cristina answers "Yes, I'm the witch." At this point Cristina closes her eyes and End p. 9 Luisa and Rosa move closer and closer toward her, almost touching her. As they approach, Cristina repeats "Colore! Colore! Colore!" (Color! Color! Color!). Luisa and Rosa move closer with each repetition and then Cristina shouts "Viola!" (Violet!). Luisa and Rosa run off screeching, and Cristina, with her arms and hands outstretched in a threatening manner, chases after them. Luisa and Rosa run in different directions and Cristina chases after Rosa. Eventually Rosa runs up to and touches a violet object (a toy on the ground), and she has reached home base. Cristina turns to look for Luisa and sees that she also has found a violet object (the dress of another child). Cristina again closes her eyes and repeats, "Colore! Colore! Colore!" The other two girls begin a second approach and the routine is repeated, this time with gray as the announced color. Rosa and Luisa again find the appropriately colored objects before Cristina can capture them. At this point, Cristina suggests that Rosa be the witch and she agrees. The routine is then repeated three more times with the colors yellow, green, and blue. Each time the witch chases but does not capture the fleeing children. Finally, Cristina suggests that they join some other children, who are playing nearby with buckets and shovels. Rosa and Luisa agree and the routine ends.

In example 1, the identification phase of the routine begins when Beth notices Steven with the bucket on his head and calls him a walking bucket. Steven had no prior history of placing a bucket on his head in this fashion. Beth just happened to see Steven while rocking on the playground boat with Brian and Mark and spontaneously identified him as a walking bucket. Her identification is confirmed by the other boys, who turn to look at Steven, and by Brian's verbal response, "Yeah."

Although the identification phase is behaviorally very simple (i.e., a call for attention, shared attention, labeling, and confirmation), the children's actions here are very important for the continued enactment of the routine. The identification provides an interpretive frame for Steven's behavior in line with the shared routine of approach-avoidance. Once the identification has been offered and ratified, the routine literally clicks into operation. A shared routine has been initiated, and its continued enactment End p. 10 is in the control of the three children who have not only labeled the threatening agent but also embraced the roles of threatened children.

The approach phase of the routine begins with Brian's suggestion, "Let's get off," which is followed quickly by all three children getting off the rocking boat and slowly moving toward Steven, with Mark in the lead. Although Steven appears to be aware of the approach, he does not react until Mark and Brian push the bucket and attempt to lift it. At this point Steven flips the bucket off his head and the three children screech loudly in mock fear. Several things are important here in terms of the routine's significance in peer culture. It is clear that the three children are in this together. The approach is communally orchestrated, from Brian's proposal, to the slow advance toward Steven, to the pushing of the bucket, and finally to the feigned fear in reaction to Steven's removal of the bucket from his head. There is a building tension in the approach phase that the children have created and share.

Steven's participation to this point has been minimal. He was thrust into the role of threatening agent by the others and was not even aware of this assignment until they pushed the bucket and he removed it. What he saw at that point was the other children pretending to be afraid and fleeing from him. In the videotape we can see that Steven actually begins to replace the bucket on his head as he notices the children's pretended alarm and their speedy movement away from him and back toward the boat. The children's fleeing initiates the avoidance phase, which can only proceed with the threatening agent's active participation. Steven flips the bucket to the ground and pursues the children while flailing his arms in a threatening manner. He pursues the children to the rocking boat, but in an admission of a limitation to his role as threatening agent, he does not move onto the boat. The boat, thus, becomes a home base for the threatened children.

With Steven's recognition of the home base and return to the bucket, one implementation of the routine has been completed. Another implementation--recycling through the same events--depends on a decision by the threatened children to initiate a new approach.

As in the prior phases, the themes of communal sharing and control are apparent. In the avoidance phase the threatened children relinquish a certain amount of control as they flee from the Walking End p. 11 Bucket. They share the tension and fear during the flight, but they know that they are in ultimate control because of the existence of the home base. Steven's pursuit of the children in a threatening manner and his recognition of the home base signal that he is also playing and that he understands the rules of the routine.

As we can see in example 1, the approach and avoidance phases of the routine are repeated several times. This example is different from several others in Corsaro's (1985) data in that an aggressive incident leads to its termination. We will discuss this departure from the normal enactment of the routine later in the paper.

Example 2 highlights some additional implications of the approach-avoidance routine for children's peer culture. First, it allows for the personification of the feared (but fascinating) figure la Strega (the Witch) in the person of a fellow playmate. The fact that la Strega is now objectified in the actions of a living person is tempered by the fact that the animator is, after all, just Cristina (i.e., another child). The feared figure is now part of immediate reality, but this personification is both created and controlled by the children in their joint production of the routine.

Although there is a wide variety of threatening agents in approach-avoidance routines, the most frequent are monsters. The Italian children Corsaro studied frequently talked about la Strega. One little girl explained that witches do not really exist, that they are per finta (for pretend). But she later pointed out that "la Strega e il Dracula sono gli amici" (the Witch and Dracula are friends). Her view of la Strega symbolizes the children's attraction to monsters. Monsters do not really exist, but we can pretend that they do. And this pretense often has a tinge of reality. For children, monsters generally represent the unknown, and in this sense they are feared. But at the same time, children have an attraction to and a curiosity about monsters. Thus, monsters are often incorporated into approach-avoidance routines.

A second thing to note is that the structure of the routine leads to both a build-up and a release of tension. In the approach phase, la Strega relinquishes power by closing her eyes as the children draw near to her. The tension builds, however, as the Witch repeats the word colore, because she decides what the color will be and when it will be announced. This announcement signals End p. 12 the beginning of the Witch's attempt to capture the children and the avoidance phase of the routine. Although the fleeing children seem to be afraid in the avoidance phase, the fear is more feigned than real, since objects of any color can be easily found and touched. Thus, the Witch seldom actually captures a fleeing child. In fact, threatened children often prolong the avoidance phase by overlooking many objects of the appropriate color before selecting one.

We see in these two examples that the threatened children have a great deal of control. They initiate and recycle the routine through their approach, and they have a reliable means of escape (i.e., home base) in the avoidance phase. These cross-cultural data nicely demonstrate how children cope with real fears by incorporating them into peer routines they produce and control.

The above interpretive analysis of the approach-avoidance routine provides insights into peer culture by focusing on the significance and meaning of these innovative performances in the everyday lives of young children. However, it fails to explain specific incidents systematically. The complexity of the underlying structure of the event is glossed over in general references to the three phases of identification, approach, and avoidance. The insights of the interpretive analysis need to be articulated with a more focused examination of the routine's underlying event structure. As we will argue more below, such an articulation followed by a reanalysis of the routine not only allows for a more objective evaluation but can also increase the interpretive power and scope of the analysis.

The process of entering data on events and relating entries can overwhelm an analyst, because a great deal of data management and meticulous reasoning are required. We use a program named ETHNO1 (Heise and Lewis 1988), which conducts complete and very efficient elicitations, asking all required questions and avoiding needless questions even in complex systems with scores of events. The program does not ask if the last entered event is a prerequisite End p. 13 for any earlier event because it assumes that events are entered in serial order. Moreover, once the program obtains some knowledge about the domain, it does not query about logical relations it can infer on its own.

The program elicits event structures as follows. First it asks what the next event is, leaving the definition entirely up to the culture expert. Then the program asks how that event relates to the events entered previously. That is, it asks, Is a specific prior event (or something similar) essential for the current event? In other words, the program asks the expert which prior events are prerequisites for the last event entered. In this way, the program taps the expert's knowledge in order to define the logical structure. (Sometimes an event has substitute prerequisites, anyone of which will do, which is why the phrase or something similar is in the relational question. The expert answers "yes" if the prior event can act as a prerequisite even if another event could serve as a prerequisite.)

The process of entering events and specifying prerequisites continues until all events in an episode are incorporated into a model.

In the next phase of analysis, the analyst returns to the event sequence to extract more information from the data, which can be used to improve the model. ETHNO also conducts this "series analysis" by working sequentially through each event to see if the sequence is allowed by the event grammar. When a problem is encountered, ETHNO offers feasible solutions and lets the analyst select one.

Specifically, the program does the following during a series analysis. First, it determines which events can initiate a series of events because they are events with no specified prerequisites. These events are highlighted on the logical graph displayed on the computer screen. The program "implements" the first recorded event by marking it as accomplished, then revises the set of events that are now possible (allowing that the first event may be the sole prerequisite for some other events).

The program implements the next recorded event. Once again, it marks the event as accomplished and revises the set of other events that are now possible. Also, the program "depletes" any prerequisite of the current event, marking it as not accomplished any more because the current event used it up. The program works through each recorded event in this way. End p. 14

The program typically encounters an event that is recorded as having happened but that could not have happened according to the event grammar either because it is not properly primed (i.e., its prerequisites are not fulfilled) or because it was accomplished previously and has not been used. ETHNO presents the problem and then offers solutions.

Possible solutions to the problem of an unprimed event are as follows:

1. Make the current event's prerequisites disjunctive so that all prerequisites do not have to be accomplished at once to properly prime the current event. This solution is offered only if at least one of the current event's prerequisites is accomplished.

2. Change the consequences of an unaccomplished prerequisite. If the prerequisite is not really a prerequisite for the current event, then the problem is solved, because the prerequisite event does not have to be accomplished before the current event. Alternatively, if the prerequisite for the current event is also a prerequisite for some other event, then maybe the prerequisite was depleted by the other event, and changing that relation would leave the prerequisite undepleted for the current event. ETHNO checks to make sure that a change in the logical structure would solve the specific problem before presenting such a suggestion.

3. Modify the depletion assumption for a prerequisite that was accomplished but that was depleted by some consequence. If this is a feasible solution, ETHNO allows the analyst to mark the relation between the prerequisite and one or more of its consequences as nondepletive.

4. Allow that an occurrence of the needed prerequisite might have occurred without being recorded. ETHNO suggests this only if the needed prerequisite is properly primed so that it could have occurred. If the analyst selects this option, the data record is modified to include an unrecorded occurrence.

Possible solutions to the problem of an unused event are as follows:

1. If the current event is in a disjunctive set of prerequisites, reinterpret the last occurrence of the consequence so that it End p. 15 uses up the current event rather than another event in the set.

2. Change the logical structure so that the current event is a prerequisite for some event that recently occurred. Then the current event is depleted and the problem is solved.

3. Modify the repeatability assumption for the current event: Allow the current event to be repeatable without depletion.

4. Allow that a consequence that uses up the current event might have occurred without being recorded. ETHNO checks to make sure that such an event is possible and then allows the analyst to change the data record.

ETHNO almost always provides an acceptable solution to a problem. After implementing the analyst's choice, ETHNO returns to the beginning of the series and works through previous events again to make sure that the solution fits all data and then continues on to subsequent events. On rare occasions, ETHNO offers no acceptable solutions. This is a cue that the episode should be reformulated with different definitions of events.

The process of entering events in the first cycle (i.e., the first enactment of key activities) for the Walking Bucket example is summarized in Table 1 (see end of chapter). The entry process for the remainder of the example is summarized in the appendix. To help the reader follow the analyst's decision making in entering the example, we have placed the transcript of the first cycle of the routine (see section 3.1) on the left side of the page in Table 1 and decisions regarding the phrasing of events for entry into ETHNO and responses to the program's questions on the right side.

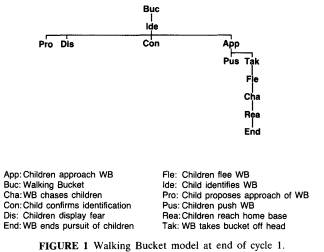

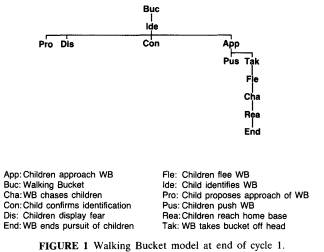

Figure 1 depicts the ETHNO graph for the first cycle of the Walking Bucket routine. ETHNO represents an event on the graph by an abbreviation: the first three letters of the second word of the phrase describing the event (because the second word is usually a verb describing the action). The lines on the graph show relations between events. We can describe the lines in either of two ways. When a line connects two elements, we can say that the higher element is a prerequisite for the lower, or we can say that the lower implies the higher. We can see in Figure 1 that the basic elements in the End p. 16 underlying event structure of the routine branch to the right side of the graph. Push is an embellishment of approach and branches from it, while confirm, propose, and display are all optional actions that depend only on the identification of the threatening agent.

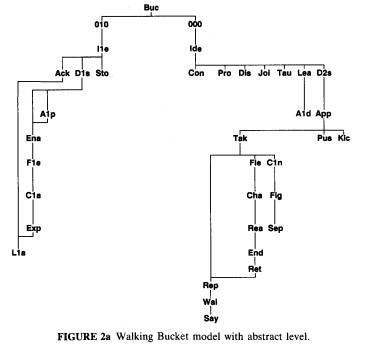

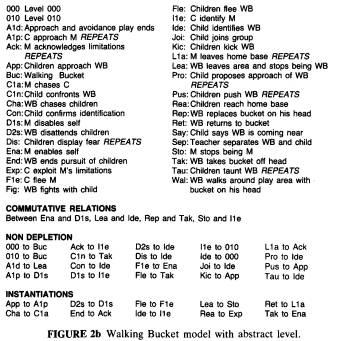

Figure 2 shows the graph produced by ETHNO once all the events have been entered and all the questions regarding prerequisites have been answered (see section 6.1.). The relevant part of the graph is the structure descending on the right. (Figure 2 also incorporates some features from the series analysis, and the structure descending on the left represents an abstract version of approach-avoidance, as explained later in section 6.)

Table 2 (see end of chapter) presents a portion of the ETHNO series analysis for the Walking Bucket example to illustrate the kind of dialogue that occurs between computer and analyst.

Earlier we noted the importance of culture for defining and entering events in ETHNO and argued that models are best constructed from records of behavioral routines interpreted with the aid of culture experts. Tables 1 and 2 and the appendix present this process in detail. Here we wish to emphasize the complexity of this task. Translating observed episodes into sequences of elementary events requires interpretations of audiovisual data, detailed transcripts of these materials, field notes of actual events, and informal interviews of informants. The phrasing of events for entry into End p. 17 ETHNO requires repeated viewings and examinations of the various ethnographic data, discussions with cultural informants, and numerous modeling attempts. Event structure analysis demands precise and meticulous descriptions of highly complex interactive materials. The complexity of this task is virtually ignored in social scientists' analyses of survey and demographic data, which depend on similar codings, summarizations, and interpretations that are often assumed to be unproblematic.

Several entries in Table 1 illustrate how verbal and nonverbal events are interpreted in both local and more general cultural contexts to insure that their underlying cultural logic is semantically preserved in the descriptions. Consider the second entry, Child identifies Walking Bucket. This description is based on the culture expert's interpretations of a series of verbal and nonverbal acts that appear to the left of the entry. ETHNO is not designed to address the verbal content of exchanges embedded in events. On the contrary, the verbal content is interpreted by the expert, who preserves context at several levels.

At the level of the local scene, Beth's exclamation "Hey, a walking bucket! See the walking bucket!" and its repetition with slight modification and pointing after the other children's nonverbal behavior and questioning were important in the identification of the object of attention as a walking bucket. In accepting the child's label (walking bucket), the culture expert stays very close to the local scene (the setting, the participants, and their verbal and nonverbal behaviors as recorded on the videotape). Someone unfamiliar with these children or peer culture may have used the same phrasing.

On the other hand, Beth's choice of the label walking bucket over several alternatives (e.g., "Hey, that kid [or Steven] has a bucket on his head!") is important to the culture expert. Labeling Steven a walking bucket generally identifies him as a monster or a threatening agent, which has specific meaning in the larger peer culture. Thus, in the judgment of the culture expert, Beth's verbalization may go well beyond the simple labeling of what she sees in the local context. In fact, the culture expert sees the labeling as identification, which is an essential element in the enactment of the shared routine.

If we look at the fourth entry in Table 1, Child proposes approach of Walking Bucket, we can see even more clearly how End p. 18 the program depends on the culture expert's contextualization (Gumperz 1982) of verbal material. The culture expert summarizes Brian's suggestion, "Let's get off," as a proposal to approach the Walking Bucket. Although the content of this speech act is indeed a proposal, at a local or surface level it would be interpreted as a proposal to get off the boat, not as a proposal to approach the Walking Bucket. It is the phrase's sequential placement after identification and before an actual approach and the culture expert's knowledge of the complex negotiations that often occur in the approach phase of the routine that leads to the summarization Child proposes approach of Walking Bucket.

Although we do not have space to further illustrate the complex decision making involved in using ETHNO, these two examples (along with Tables 1 and 2 and the appendix) provide some insight into event structure analysis. It should be clear that although the program produces formalized logical structures, the basis of these structures depends on the systematic interpretive work of the ethnographer.

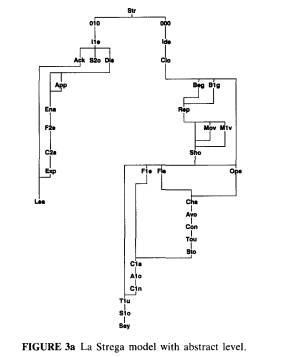

As we did for the Walking Bucket, we abstracted events for la Strega (see example 2), entered them into ETHNO, and ran a series analysis. Figure 3 depicts the ETHNO graph for la Strega once all the events have been entered, all the questions regarding prerequisites have been answered, and the series analysis has been completed (see section 6.1.). (The relevant portion of the graph is the part descending on the right; the part descending on the left represents generalized approach-avoidance.) We do not have space to discuss our modeling of la Strega in the same detail that we discussed the Walking Bucket. We will, however, make a number of points about some of the differences between the two models in the next section of the paper.

There are a number of cautionary points we should make about our analysis of la Strega. First, we have no video recordings of enactments of la Strega, as we had for the Walking Bucket and other versions of approach-avoidance. We have relied, instead, on field notes that summarize various enactments that were observed in Italy. Given the formalized nature of the routine, these field End p. 19 notes may not have captured subtle embellishments or variations in the production of the routine, and until a planned video recording of la Strega is completed, we cannot be sure of the overall validity of our analysis. Second, we do not know whether differences between la Strega and the Walking Bucket are due to the formalized features of la Strega or to cultural factors. Although spontaneous approach-avoidance routines have been observed in Italy, we have yet to record any spontaneous enactments on videotape. A rigorous investigation of possible cultural differences depends on the collection of these needed video data.2

Having entered events, determined logical relations, and run series analyses on the Walking Bucket and la Strega data, we can now reconsider our initial interpretation of the significance of the approach-avoidance routine in peer culture. We begin with the Walking Bucket. Several aspects of the event structure and the series analysis have important implications for our earlier interpretation: identification (as a key or triggering event in the routine), the demarcation of the approach and avoidance phases of the routine, and the nature and significance of recycling.

Identification. As we entered events and determined logical relations, we discovered that a number of events (confirmation of identification, proposal for approach, displays of fear, taunting, joining, and leaving) were dependent on identification but were not essential for any other event in the routine. We decided that their occurrence was optional and that they amplified or embellished the End p. 20 routine in various ways (see Table 1 and the appendix). In running the series analysis (see Table 2), we consistently ran into problems regarding these actions, which we handled by deciding that all of these events (except for leaving) did not deplete identification. We also decided that identification can only be depleted when the threatening agent stops playing the game, i.e., when he or she leaves the area and stops being the Walking Bucket. Since this case involved a special pattern of depletion, the program checked to see if identification and leaving had a commutative relationship, in which each primes the other. We answered "yes" to this question because once a child stops being a threatening agent, the routine can, in principle, be restarted with another identification (see Table 2).

In running the series analysis, however, we did more than simply deal with problems of depletion and commutative relationships. Solving these problems made us aware that it was the nature of these various actions in relation to the identification frame that was important and not so much where they occurred in the sequential structure of the routine. Earlier we noted that identification signals that the approach-avoidance routine is underway and activates the children's shared knowledge of the basic structure of the play routine. Although the related actions under discussion here can occur only after identification, they are not essential to the basic sequential script. Most of these actions (confirmation of identification, proposal for approach, displays of fear, and taunting) are optional embellishments of the routine, while others (joining and leaving) articulate or contextualize knowledge of the sequential script with local features of the interactive scene (see Cicourel 1980 and discussion below).

Embellishments are crucially important for peer culture because they allow for individual creativity within the bounds of collectively shared knowledge. On the other hand, many of these innovative embellishments serve to emphasize the communal significance of the routine. For example, certain embellishments (confirmation of identification and proposal for approach) increase the spirit of cooperation in the routine. These optional negotiations among the threatened children accentuate the importance of group cohesiveness in the recognition and later confrontation of the danger. This finding led us to inspect other examples of approach-avoidance in the data base, whereupon we discovered several cases End p. 21 of prolonged negotiations regarding identification and approach strategies (see Corsaro 1985, pp. 232-35, for one such example).

Other embellishments (displays of fear and taunting) enhance the tension and danger embedded in the structure of the routine. These embellishments can occur anytime after the threatening agent is identified, and they enable the children in the threatened role to exploit or transform the basic script. Here, terminology from Goffman's Frame Analysis is useful. The basic sequential script of the routine can be seen as a keying of a primary framework in children's lives (i.e., real dangers or threatening agents), while the embellishments can be seen as rekeyings (second transformations) of the initial keying (i.e., make-believe or pretend [see Goffman 1974, pp. 40-48]). Exaggerated displays of fear and taunting of the threatening agent (rekeyings) serve dual functions: TThey make the activity seem more real while reminding the children that it is, after all, just pretend.

Moving through the mechanics of ETHNO (entering events, determining logical relations, and running a series analysis) led us to discover additional complexities in the identification phase of the routine. The identification of a threatening agent activates the basic sequential script of the routine and also primes the developing interactive scene for creative embellishments. Here we see that shared knowledge of the basic event structure not only insures predictability and security but also empowers the routine by providing a frame within which a wide range of embellishments can be produced, displayed, and interpreted.

Approach. Earlier we argued that two key aspects of the approach phase were the children's caution in their movements toward the threatening agent and the threatening agent's lack of attention to the approach until the children drew very close. From the Walking Bucket video it is clear that the threatened children cautiously approached the threatening agent as a group. Although the Walking Bucket could hear and sense the approach of the other children, his vision was impaired by the bucket, and he did not respond until two of the threatened children pushed the bucket.

In entering events and determining logical relations, we decided that the pushing of (and later kicking at) the Walking Bucket were optional embellishments of the approach. Therefore, we designated nondepletion from push and kick to approach (i.e., End p. 22 push and kick were dependent on approach but they did not end it). In short, we felt that the threatening agent would have eventually responded to the approach without these embellishments but that their occurrence increased the drama of the approach phase. Responding to the program's questions about push and kick led us to view the video of the approach phase numerous times, often playing back the tape in slow motion. These viewings showed that the children were cautious in these embellishments. For example, after pushing the bucket, the children jumped back, anticipating a response from the threatening agent. Even more interesting is the fact that the children never actually kicked the Walking Bucket but kicked at (and barely missed) his legs several times. We again see the innovative character of embellishments. In this case the cautious approach frame is rekeyed to one of controlled daring. The sense of danger is magnified within the constraints of the play frame.

As we note in Table 1, the program forced us to consider the complex nature of the event, Walking Bucket takes bucket off his head. As we answered questions about logical relations and ran the series analysis (Table 2), we discovered that (1) the presence of the bucket disables and makes the threatening agent approachable; (2) the removal of the bucket enables the threatening agent and signals the end of the approach phase; and (3) this enabling is dependent on the approach of the threatened children. Thus, the detailed micro-decision-making demanded by the program was crucial in the specification of our earlier general claim that the threatened children have a great deal of control over the enactment of the routine.

Avoidance. We gained several insights from our response to ETHNO questions regarding the avoidance phase of the routine. All of these insights are related to the subtle coordination of actions between the threatening agent and the threatened children. First, we had to deal with what initially seemed to be an obvious relation between chase and flee. As we entered events the program asked, "Is Flee essential for Chase?" (see Table 1). On the surface it seems that the question should be the other way around: One flees a threatening agent because one is chased by the threatening agent. However, when we thought more about the question and viewed the Walking Bucket and other videotaped examples of approach-avoidance, it became clear that fleeing was essential for chasing and End p. 23 not vice versa. In fact, sometimes the threatening agent was an inanimate object and the children still fled, pretending that they were being pursued. As we noted earlier, the child in the role of the Walking Bucket was actually beginning to place the bucket back on his head when he noticed the other children fleeing toward the rocking boat. He then dropped the bucket, visibly took on a threatening manner, and chased the fleeing children. Again we see that the threatened children had implicit control, since pursuit was dependent on flight in this routine.

A similar type of coordination occurs when the children reach the safety of the home base. In this example, and in most occurrences of approach-avoidance (but see the discussion of la Strega below), home base is not specified in advance. Thus, the pursuit continues until the threatened children discontinue their flight and "offer up" a home base for ratification. This is usually accomplished by actions such as hiding behind a tree, moving into the climbing bars, or hopping up on playground equipment (e.g., the rocking boat in the Walking Bucket example). To answer the program's questions regarding the relation between ending the pursuit and reaching home base, we looked very closely at the videotape. We found that in the first cycle of the routine, the threatening agent moved very near and actually touched home base but made no attempt to enter the space and continue the chase. In later cycles he often abruptly ended pursuit without these subtle acknowledgements of limits to his power that are embedded in the notion of a home base (see the discussion of la Strega below).

Recycling. Earlier we noted that the approach and avoidance phases of the routine are often recycled. However, the significance of such recycling and how it is initiated and terminated in specific occurrences of the routine were not clear. Entering events and running a series analysis on the Walking Bucket example aided our understanding of recycling. For example, ETHNO helped us to see that recycling presents multiple opportunities for embellishing the routine. Specifically, we found in the series analysis (Table 2) that certain events (e.g., displaying fear and taunting) can be repeated without depletion. These events are not prerequisites for other events; i.e., they do not prime and are not depleted by other specific events. They can, instead, occur at any point in the routine once the threatening agent is identified. Recycling, then, widens the End p. 24 parameters of opportunity for embellishment and, thus, increases the productive power of the routine for the children. It does not seem repetitive or redundant from the children's point of view. Recycling is, instead, a common and much enjoyed feature of the routine.

Approach-avoidance routines cannot, however, be recycled at any point in their sequential structure, nor are they recycled indefinitely. Portions of the Walking Bucket routine were recycled twice, and a third recycle was initiated but was not completed. Entry of the example into ETHNO demanded the precise specification of features of recycling (see the appendix). As we noted in our earlier description and interpretation of the routine, only the approach and avoidance phases of the routine are recycled. In his data, Corsaro (1985, 1988) observed no instances of re-identification of the original threatening agent. In addition, there is a certain logic to the claim that initial phases of routines generally establish or activate a framework within which the more dynamic elements transpire and that these initial phases are often omitted in recycling (see Goffman 1971,1974,1981).

In the Walking Bucket example, however, recycling was more complex than the simple reapproach of the Walking Bucket after the avoidance phase. In fact, in responding to questions from ETHNO we decided that repetitions of the approach phase were dependent on the threatening agent returning to the bucket and replacing it on his head. In this sense, there was a commutative relation between take and replace. Once the bucket was replaced, the threatened agent returned to his original disabled state, a new approach was initiated, and a new avoidance phase was signaled via the removal of the bucket (enabling of the threatening agent). In reanalysis of the example we see that this enabling-disabling process was very important in the production and recycling of the routine.

Modeling the Walking Bucket in ETHNO also led us to consider two sets of issues regarding the termination of approach-avoidance routines. First, in responding to questions from the program we decided that if the threatening agent leaves the play for any reason, the routine ends. If a new threatening agent is identified or a previous one is re-identified, then a new production (not a recycle) of the routine occurs. Thus, in the Walking Bucket routine, identification of the threatening agent and the threatening agent's End p. 25 exit from the area (and his abandonment of the Walking Bucket role) had a commutative relationship: i.e., each primed the other. The specification of the relationships in this way allows for the demarcation of novel productions of the routine and recycles.

Second, a routine may also end as the direct or indirect result of actions by the threatened children. For example, the threatened children may decide not to recycle the routine with a new approach phase, or they may disrupt a production of the routine by challenging rather than fleeing from the threatening agent. Such disruption occurred in the third recycle of the Walking Bucket example. As the threatened children approached the Walking Bucket for the third time, he removed the bucket before the other children reached him to touch or push it. This early enabling of the threatening agent may have confused one of the children, who did not flee with his playmate but instead confronted the Walking Bucket. This alteration in the routine led to a series of events: a brief fight; intervention by a teacher, who separated the boys; the departure of both boys from the play area; and the termination of the routine (see the appendix and Table 2 for details). The termination of the Walking Bucket example nicely demonstrates how a specific deviation or disruption can interact with other elements to short-circuit and terminate the routine.

The primary benefit of modeling la Strega is that it allows us to compare productions of the approach-avoidance routine in two cultures. Although the graph for la Strega looks quite different from the one for the Walking Bucket (see Figures 2 and 3), many of the differences can be directly linked to the formalized nature of the Italian example. First, unlike spontaneous versions of approach-avoidance (in the U. S. and in Italy), children in la Strega are seldom thrust into the role of threatening agent. Identification is usually a matter of simple negotiation among the players, and all of the children have a turn as la Strega over multiple enactments of the routine. Second, la Strega does not ignore the advance of the threatened children but rather formally disables herself by closing her eyes. Furthermore, the Witch's repetition of the world colore is a clear signal that the approach should continue. Third, the Witch End p. 26 simultaneously shouts the name of a color and uncovers her eyes. With these actions the Witch formally identifies and ratifies home base (i.e., acknowledges limits to her power) and enables herself to chase the fleeing children before they can reach home base.

One result of these formalized features of la Strega is that they do not give the children the opportunity to embellish the routine. This lack of embellishment in la Strega is a central difference between the two models (see Figures 2 and 3). For example, there is little need for the threatened children to negotiate an approach of the Witch, since she clearly disables herself and signals that the children should draw nearer by repeating the word colore. Additionally, the formal identification of home base eliminates the need for subtle negotiation between the threatening agent and the threatened children.

A second result of the formalized nature of la Strega is that the threatened children are less dependent upon one another to communally orchestrate a version of the routine that is in line with its underlying structure but responsive to local features of the interactive scene. The threatened children flee along separate paths from the Witch, who pursues one and then the other. Thus, we see two separate branches of the avoidance phase in the la Strega routine: (Fle-Cha-Avo-Con-Tou-Sto and F1e-C1a-A1o-C1n- T1u-S1o: see Figure 3). There is only one such branch in the Walking Bucket routine: Fle-Cha-Rea-End-Ret (see Figure 2). Nevertheless, the main elements of the avoidance phase are very similar in the American and Italian versions of the routine.

Finally the formalized nature of la Strega often limits possible recycling of the routine, as it did in this example. Although there may be several re-enactments of la Strega, with children taking different turns as the Witch, we rarely found instances in which one child was the threatening agent for multiple cycles of the routine.

The modeling of the Walking Bucket and la Strega routines in ETHNO and the reanalyses have led to the specification of several important features of the event structure of the approach-avoidance routine that were glossed over in the original analysis.

The models we have developed to this point are so specific that they can be used only for analyzing approach-avoidance in one End p. 27 episode at a time. For example, details like the following tie the Walking Bucket model to a single time and place.

First, the character identifiers are too unique to be found elsewhere. In particular, we will probably never observe another approach-avoidance episode involving a walking bucket. (Other participants in the events are identified as child or children, but they were referred to by name in our first model of the episode. We generalized their identities to reveal cycling in the episode.)

Second, some key actions in the episode are described in such detail that they could occur only in the original setting or in a very similar setting. For example, Walking Bucket takes bucket off his head is the point at which the strange creature enables himself and becomes dangerous. An event like this is a crucial part of approach-avoidance play, but in other cases, we will not find enablement occurring through removal of a bucket.

Third, some events, like Children kick at Walking Bucket, are behavioral embellishments that develop in the special circumstances. Such events could occur in other performances of the routine, but they might not; and different embellishments might occur elsewhere.

Fourth, some events, like Walking Bucket replaces bucket on his head, are instrumental activities that must be accomplished before this specific rendition of the routine can occur. The event is important in the Walking Bucket model, but it is impossible in other cases.

Finally, some events, like Child joins play, and some side episodes, like the fight terminated by a teacher, are extraneous to the approach-avoidance routine. These particular happenings developed from the unique configuration of characters in the setting at the time.

The la Strega model is similarly limited in its application by the same kinds of factors and by another problem. Cyclings in la Strega require orderly replacement of a participant: The flee and chase sequence involves first one child, then the next. In most other instances of approach-avoidance, children flee together and are chased as a group.

Despite the specific differences, the Walking Bucket and la Strega routines are basically the same. To show the similarity, we need to abstract a higher-level model that represents the essential features present in both of the concrete models. Abstraction has to End p. 28 address the problems noted above, and we offer the following guidelines for abstracting a generalized model.

1. Generalize participants' identities in event descriptions so they can be applied to different episodes and to different cycles of the same episode. For example, refer to the Walking Bucket and to la Strega as monsters. Refer to child A and child B as children.

2. Describe actions in terms of their general purpose for the routine. For example, replace the phrases takes bucket off head and opens her eyes with enables self.

3. Ignore embellishments, concrete instrumental activity, and particularistic happenings. The higher-level model should deal only with essential parts of the routine.

These operations yield a reduced set of events phrased in general terms. To form a model, we must conduct the elicitation process again at the higher level of abstraction, entering the abstract events and specifying which abstract events are prerequisites for others. We use ETHNO again for the elicitation procedure, which is comparable to that described in Table 1.

However, merely creating an abstract model does not validate the claim that the two different episodes of approach-avoidance represent one routine. We must also show that the abstract model fits the concrete sequences of events in both episodes. We must specify how concrete events translate into the events of the abstract model. That is, we must define how concrete events instantiate abstract events.

ETHNO accomplishes this by joining an abstract model to a concrete model, producing a single model with two levels, and by allowing the analyst to specify instantiation relations to determine when an abstract event will be triggered by a concrete event. ETHNO then uses the expanded model to reanalyze the original sequence of concrete events. It automatically inserts abstract events into the sequence as they are instantiated by concrete events. During this multilevel series analysis, the abstract model typically has to be adjusted-relations have to be changed or assumptions have to be modified-to fit the sequence of abstract events that is generated as the sequence of concrete events unfolds. End p. 29

We developed an abstract representation of the Walking Bucket model by following the principles listed above, and then, in the course of a multilevel series analysis, we adjusted the abstract model until it fit the Walking Bucket data. That is, we adjusted the abstract model until the concrete events not only fit the concrete logical model but also instantiated abstract events that fit the abstract logical model.

Next, we appended the abstract model to the concrete model for la Strega and defined appropriate instantiations of the abstract events by concrete events within la Strega. Again, we conducted a series analysis and made changes in the abstract model until it fit the la Strega data.

One more iteration back to the Walking Bucket episode produced the two-level models shown in Figures 2 and 3. Figure 2 shows the Walking Bucket model at the lower level, and Figure 3 shows the la Strega model at the lower level. The abstract model is End p. 30 identical in both figures. The abstract model's instantiation by concrete events is indicated in the lists of instantiation relations given with each figure. Note that some concrete events do not instantiate any abstract events: Embellishments, instrumental activity, and particularistic happenings transpire without abstract significance.

The single abstract model accounts for key events in both examples of approach-avoidance. Thus, it is possible to define a grammar of action that accounts for widely discrepant instances of approach-avoidance play: Italian versus American, informal versus formal.

One striking feature of Figures 2 and 3 is how different all of the submodels look. The models of concrete activity have obviously different structures, and neither of them looks much like the abstract structure that provides a higher-level interpretation. In essence, this End p. 31 means that the logic of concrete scenes varies from one episode to another and that an abstract model can have a logic that only vaguely resembles the logics of concrete happenings. Nevertheless, an abstract model is related in a disciplined manner to its concrete source models. In our approach, the abstract model must identify actors and actions in more general semantic terms, and it must account for a subset of events in each concrete event sequence.

Abell (1987) suggests that a proper abstract rendition should be homomorphically related to more concrete renditions. The particular homomorphism that Abell favors would not work here because it does not permit cycling (and we have not yet arrived at the definition of a homomorphism that would apply to our cyclical approach-avoidance data); but treating abstract renditions as homomorphic reductions seems a promising approach to disciplining the abstraction process, beyond the procedures we have defined. End p. 32

Event structure models at the concrete level represent knowledge applied by local actors in the sense that the models display acknowledged constraints and opportunities surrounding each event. Whether a similar claim can be made for abstract models is uncertain. On the one hand, local actors may infer abstract events and event relations from experiences and thereafter articulate their abstract knowledge in other contexts, since abstraction is largely a matter of semantic generalization and of ignoring some details. On the other hand, abstract models that are cross-culturally based (like the one we have presented) result from encountering episodes beyond the cognizance of anyone local actor. In such cases the abstract model still represents knowledge, but it may represent knowledge that arises only in a culture of scientists rather than knowledge that is available indigenously in the groups that were studied (Latour 1987).

The method of event structure modeling, as presented in this paper, has benefited from developments in ethnographic research within sociology and cultural anthropology. But we feel that our method moves beyond some of the limits of these approaches in several respects.

We agree with ethnoscience's contention that there is an underlying logic to cultural knowledge and process, and we agree to some extent with its reliance on formalized methods of data analysis. But we do not endorse ethnoscience's definition of culture as an underlying cognitive system dependent on the mental competence of natives. In line with Geertz (1973, 1983), we view culture as the public interpretation of an ambiguous text.

While accepting the metaphor of culture as text, we have attempted to overcome the reliance on "stylistic virtuosity" (see Crapanzano 1986) that typifies much of interpretive ethnography and sociological field research. Research in interpretive anthropology often involves detailed descriptions of key events and rituals followed by an interpretation of the meaning and cultural significance of such events. However, these initial descriptions are not usually of specific events or the actual performance of rituals, but rather are based on a summarized or constructed ideal type. In much of sociological field research, the problem is somewhat the reverse. Theoretical concepts and propositions are discussed at an abstract level and examples that illustrate the concepts or propositions are selected from field notes, with little discussion of representativeness or the mechanics of data analysis.

The problem here is that a highly complex and somewhat messy world is cleaned up and articulated as an ideal type or illustrative example that is ripe for the analytic genius of the ethnographer. We do not wish to devalue the importance of interpretive and qualitative analysis; rather, we offer a method that forces the analyst to deal with actual performances.

Consider our analysis and later reanalysis of the Walking Bucket instance of the approach-avoidance routine. We began with the presentation of an actual example and an initial interpretation End p. 34 based on Corsaro's (1985) earlier work. However, this was not so much an interpretation of the actual example as it was Corsaro's intuitive grasp of a more general structure of the approach-avoidance routine that the Walking Bucket illustrated. In this sense, the original interpretation was, to a large degree, a reconstructed version of the routine and suffered from some of the problems we noted above.

In the reanalysis, we focused on an actual performance of the routine, the videotape of the Walking Bucket. In the first phase, we entered specific events of the actual performance into the ETHNO program, determined logical relations, and then ran a series analysis. This required that we examine the actual performance of the routine in excruciating detail and involved a considerable investment of time and energy. We had to re-examine the videotape numerous times and look for specific types of information that seemed inconsequential or that were taken for granted in the original interpretation. Also, Corsaro re-examined his field notes and other video data and called on his knowledge of the setting in which the event occurred. In the second phase, we interpreted the program's analysis of the actual performance. As we discussed previously, this interpretation did not contradict the earlier one generated without the program. But it did expand its interpretive power in several important respects.

Having completed a detailed analysis of a specific occurrence of the approach-avoidance routine using the ETHNO program, we then analyzed a second instance of the routine produced in a different culture (la Strega). In the final phase, we successfully extracted an abstract model that accounted for both events. Our success here is impressive given that the specific events were quite different at the concrete level.

In sum, the method enabled us to model actual performances of a play routine and to interpret its significance for peer culture without obscuring the complexity and meaning of the event from the children's point of view. Although we believe that the concrete structures that we identified reflect the children's underlying knowledge of approach-avoidance, we do not maintain that the intersubjective sharing of such knowledge will lead to automatic enactments of the event. Again, culture is not in the heads of individuals. It is produced and reproduced through individuals' public negotiations End p. 35 and activities with others. In these negotiations and activities, individuals link shared knowledge to specific situations to generate shared meanings and simultaneously use this shared knowledge (and the sense of shared culture thus generated) to make novel contributions to the culture and to pursue a range of individual goals.

Event structure models record systems of constraint that control action, and archives of such models can provide a corpus of empirically based structures for analysis of social institutions (Fararo and Skvoretz 1984). The multilevel nature of the models allows the researcher to faithfully record concrete action in particular factories, offices, stores, etc., to perform comparative analyses, and to recognize commonalities at abstract levels of analysis.

As we have demonstrated, event structure analysis is useful for the analysis and interpretation of discourse processes in rituals and other cultural routines. The method may also be useful for the study of discourse processes in medical, educational, and organizational settings. However, it does not deal directly with actual discourse, and it demands some degree of abstraction (or expansion [see Labov and FansheI1977]) from actual speech to the underlying force of speech acts. The model could be used to evaluate the logical consistency of various expansion or interpretive models of discourse analysis (see, for example, Atkinson and Drew 1979; Cicourel1987; Grimshaw 1989; Gumperz 1982; Labov and Fanshel 1977; and Mehan 1979). The approach seems, however, to have less utility for the analysis of informal conversation (see Atkinson and Heritage 1984; Sacks, Schegloff, and Jefferson 1974; Schegloff 1987).

Event structure analysis of written narratives--personal accounts, stories, novels--offers a principled basis for interpreting popular realities and popular reasoning. For example, in modeling a common folktale, Heise (1988) and Heise and Lewis (1988) show that the tale inverts normality and abnormality of action to communicate values and that a centuries-old tale still has emotional impact because the story teems with contemporary concerns at the abstract level. End p. 36

Causal theories are essentially event structure models developed by social scientists to account for patterns that recur in different times and places (Abell 1987). The methodology of event structure analysis offers several benefits to those who are trying to develop causal theories: computer-assisted construction of explicit, detailed models; systematic consideration of logical relations and metatheoretical assumptions; the potential for evaluating and revising formulations on the basis of records of observed events from field notes or historical archives; and the ability to explore implications of a theory through simulation analyses.

1 ETHNO, version 2, compiled from 8,000 lines of Pascal code, operates on MS-DOS personal computers with 5I2K of memory and either a monochrome or a color monitor. The program comes with a book of documentation and a tutorial.

2 Corsaro recently recorded several instances of la Strega on videotape while in Italy. He found two versions of the routine. One was very similar to the version recorded in field notes and described in this paper. However, a second version had a somewhat different structure involving a larger group of participants. In this second version there is a phase in the routine during which la Strega approaches and, via a sequence of questioning, identifies a specific victim from the group who must then try to escape. We are presently conducting a detailed analysis of this version of the routine. These new data demonstrate the importance of working with video data in event structure analysis.

Abell, Peter. 1987. The Syntax of Social Life: The Theory and Method of Comparative Narratives. New York: Oxford University Press.

Atkinson, J. M., and Paul Drew. 1979. Order in Court: The Organization of Verbal Interaction in Judicial Settings. London: Macmillan.

Atkinson, J. M., and John Heritage, eds. 1984. Structures of Social Action: Studies in Conversation Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Anderson, John R. 1983. The Architecture of Cognition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Axten, Nick, and John Skvoretz. 1980. "Roles and Role-Programs." Quality and Quantity 14: 547-83.

Becker, Howard S. 1958. "Problems of Inference and Proof in Participant Observation Research." American Sociological Review 23: 652-60.

___. 1963. Outsiders: Studies in the Sociology of Deviance. New York: Free Press.

___. 1970. Sociological Work. Chicago: Aldine.

___. 1982. Art Worlds. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Briggs, Charles L. 1986. Learning How to Ask: A Sociolinguistic Appraisal of the Role of the Interview in Social Science Research. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Cicourel, Aaron V. 1964. Method and Measurement in Sociology. New York: Free Press.

___ .1980. "Three Models of Discourse Analysis: The Role of Social Structure." Discourse Processes 3: 101-32.

.1987. "The Interpenetration of Communicative Contexts: Examples from Medical Encounters." Social Psychology Quarterly 50: 217-26.

Corsaro, William A. 1985. Friendship and Peer Culture in the Early Years. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

___ .1988. "Routines in the Peer Culture of American and Italian Nursery School Children." Sociology of Education 61: 1-14.

Corsaro, William A., and Thomas Rizzo. 1988. "Discussione and Friendship: Socialization Processes in the Peer Culture of Italian Nursery School Children." American Sociological Review 53: 879-94.

Crapanzano, Vincent. 1986. "Hermes' Dilemma: The Masking of Subversion in Ethnographic Description." Pp. 51-76 in Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography, edited by James Clifford and George Marcus. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Denzin, Norman K. 1977. The Research Act. Chicago: Aldine.

DiMaggio, Paul. 1987. "Classification in Art." American Sociological Review 52: 440-55.

Fararo, Thomas J., and John Skvoretz. 1984. "Institutions as Production Systems." Journal of Mathematical Sociology 10: 117-82.

___ .1986. "Action and Institution, Network and Function: The Cybernetic Concept of Social Structure." Sociological Forum 1: 219-50.

Fine, Gary. 1987. With the Boys: Little League Baseball and Preadolescent Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.